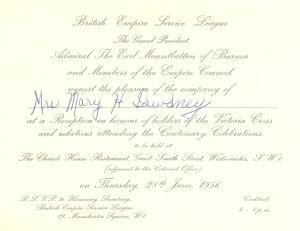

by Sam McBride

Mary Helen Peters was born in Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island on August 31, 1887. She was always known as Helen by friends and in the family, and in later years was known as Gran to her three children and ten grandchildren and many of her younger friends. The first of six children, she outlived all of them, including a younger sister who died in a fireplace accident, three brothers who died in the world wars, and another brother who had a mental disability.

At age eight in early 1898 she moved with her family across Canada by boat, trains and boat again to Victoria on Vancouver Island. The sea was a constant in her youth, as she went from an Atlantic island to a Pacific island.

She went to schools in Charlottetown and Victoria, and then in 1900 went to Bedford in north London, England where she attended the Bedford School for Girls. At the same time, her brothers Fritz and Jack attended the Bedford Grammar School. It is likely they all stayed at the home of their mother Bertha`s stepmother, Sarah Caroline Cambridge Gray, who moved there after the death of her husband, John Hamilton Gray in 1887. One of Helen`s memories from her time at Bedford was watching with her brothers on a London street in January 1901 as the funeral procession for Queen Victoria solemnly passed by.

She went to schools in Charlottetown and Victoria, and then in 1900 went to Bedford in north London, England where she attended the Bedford School for Girls. At the same time, her brothers Fritz and Jack attended the Bedford Grammar School. It is likely they all stayed at the home of their mother Bertha`s stepmother, Sarah Caroline Cambridge Gray, who moved there after the death of her husband, John Hamilton Gray in 1887. One of Helen`s memories from her time at Bedford was watching with her brothers on a London street in January 1901 as the funeral procession for Queen Victoria solemnly passed by.

clockwise, from bottom left: three images of Helen as a young lady in Victoria; with her brother Gerald in the yard of their Oak Bay home; seen with tennis friends (McBride Collection)

Helen studied piano and music at the Royal Conservatory of Music in London, and became an accomplished pianist.

One of her father`s partners in business ventures in Victoria was the Hon. Edgar Dewdney, the former trail-builder, federal cabinet minister and B.C. lieutenant governor. Dewdney was uncle and guardian of Edgar Edwin Lawrence “Ted” Dewdney, born December 26, 1880 in Victoria. Ted`s mother Caroline Leigh died when Ted was four and his father Walter Dewdney died when Ted was 11. Ted lived with his uncle Edgar and aunt Jane between 1892 and 1897 at Cary Castle in Victoria when it was the official residence of the Lieutenant Governor.

A keen student of history and literature, Ted wanted to go to university, but his uncle insisted he enter the banking world at an early age. Ted began as a clerk for the Bank of Montreal in Victoria in December 1897, and was subsequently transferred to the bank branches in New Westminster, Greenwood, Rossland and Armstrong before returning to Victoria in 1908.

Ted was athletic and an outstanding tennis player, winning the West Kootenay Tennis Championship three times in the early 1900s while residing in Rossland. Helen was also a keen tennis player and participant in tennis-related social events in Victoria. It is likely that the pair got to know each other in tennis activities or through the Anglican Church.

Ted and Helen married June 19, 1912 at St. Paul`s Anglican Church in Esquimalt, adjacent to Victoria. Her father Frederick Peters could not attend because he was tied up with his work in Prince Rupert. He asked his cousin, Colonel James Peters, to fill in for him in “giving the bride away”. Col. Peters had retired recently after an eventful 42-year career with the Canadian military, including many years in charge of West Coast defence. When he arrived in Victoria in command of the first battery to defend Victoria and the Esquimalt Naval Base he was the first of the Peters clan to settle in B.C. The wedding reception may have been something of a reunion for Col. Peters and another prominent guest, the Hon. Edgar Dewdney. Twenty-five years earlier Dewdney was Lieutenant Governor of the Northwest Territories and Minister of Indian Affairs during the Riel Northwest Rebellion, in which Col. Peters (then a captain) was in charge of an artillery battery and was honoured with a Mention in Dispatches. For further information on Col. Peters, see http://www.navalandmilitarymuseum.org/resource_pages/coastal_defence/james_peters.html.

from bottom left: cutting the cake; the wedding party; Helen beside Ted`s uncle, Edgar Dewdney; Helen (fourth from right) as a bridesmaid for a friend`s wedding (McBride Collection)

Ted and Helen moved to Vernon in the Okanagan region of central B.C., where Ted worked as an accountant with the Bank of Montreal. On Dec. 6, 1913, their first child, Evelyn Mary “Eve” Dewdney was born.

They were in Vernon at the outbreak of the First World War in August 1914.

from bottom left: Helen and Ted with children Eve, Peter and Dee Dee, 1925; four images of Helen, including her costumes for local productions of Gilbert and Sullivan`s Mikado (McBride Collection)

Her brother Fritz had left the Royal Navy in 1913 after eight years of service. With war declared, he caught a ride on a steamer going to Britain to rejoin the navy. Her other brothers Jack, Gerald and Noel had all taken militia training in Victoria and later in Prince Rupert with the Earl Grey Rifles. Each of them went to enlist in the army but only Jack was accepted. Tall and thin, Gerald`s chest measurement was below army standards so he failed the physical examination. Noel was rejected because of his mental disability, which was actually not as bad as it seemed in his appearance. Gerald went to Montreal to try to enlist, and this time he was accepted. Noel wasn`t accepted for service until May 1917 when he joined the Canadian Forestry Corps in Britain. At 33, Ted Dewdney was past ideal age for enlistment, and he was supporting a wife and child, so he did enlist. If the war had come while he was still a bachelor, he would have rushed to enlist, as he had been extremely active in the Rocky Mountain Rangers militia when he was working as a bank clerk in Rossland in the early 1900s.

In 1915 Ted the Bank of Montreal transferred Ted to its branch in Greenwood, a small mining community near the U.S. border and on the west edge of the West Kootenay region. This was his first appointment as branch manager. A year later he was transferred to manage the New Denver branch in the famous Silvery Slocan district. Housing for the manager and his family was provided in quarters above the bank, which today serves as the community`s museum.

The period from late May 1916 to late July 1916 was a time of anxiety and sorrow for the Dewdney family. First they heard that Helen`s brother Jack was not a prisoner of war as previously reported, and was now assumed to have died in April 1915 in the Second Battle of Ypres. A couple of weeks later they heard that Gerald was missing, and by early July it was confirmed that he had died in the Battle of Mount Sorrel. Helen`s mother Bertha, who had been residing in England since the late spring of 1915 so as to be close to her boys, was devastated by the deaths of two sons, particularly Gerald, with whom she was particularly close. She felt she could not return to the house in Prince Rupert with so many memories of Gerald, so she went to live with Helen`s family in New Denver. This arrangement would continue for 30 years until Bertha`s death at age 84 in 1946.

Their first and only son, Frederic Hamilton Bruce Dewdney, was born May 2, 1917 in New Denver. He was named after his uncle Fritz, and Fritz was his godfather. At an early age the boy picked up the nickname “Peter”, and he was known by that name the rest of his life. As an adult he had his name officially changed to “Frederic Hamilton Peter Dewdney”. He went by the name “F.H. Peter Dewdney” when he was the Progressive Conservative candidate in three federal elections in the Diefenbaker era. Each time he was defeated by the popular NDP incumbent MP, Bert Herridge.

The Dewdney family moved to Rossland in 1920 when Ted was transferred to manage the Rossland branch. A second daughter, Rose Pamela Dewdney, was born in Rossland June 29, 1924. She acquired the nickname “Dee Dee” and was known by that name as a teenager and throughout her adult life.

The family moved to Trail in 1927 in line with Ted`s appointment there, and then to Nelson in 1929, where Ted retired from the bank in 1940 after 42 years of service.

In each community Helen was active in organizing musical and theatrical productions using local talent. She would direct, act and play piano; Ted would be stage manager and treasurer for the productions; and they would enlist the help of people throughout the community to participate on stage or behind the scenes.

Throughout her life Helen was an ardent bridge player. She and her mother rated each community in the West Kootenay region by the quality of its bridge players.

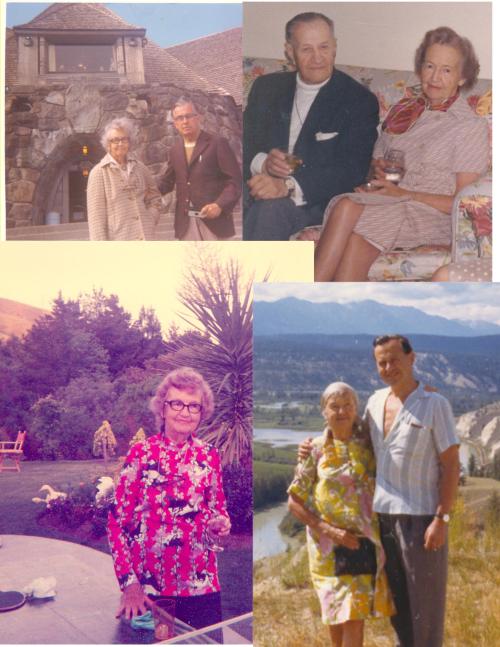

from top left: with Leigh McBride at Banff Springs Hotel; with Herbert Forbes-Roberts, father of Peter`s wife Maxine; with Peter; and in California (McBride Collection)

When Ted retired, the family had to leave the Bank House in Nelson, so he purchased a house at 820 Stanley Street in Nelson. Eve had left home in 1933 when she married Sandon, B.C.-born mining engineer Jack Fingland and moved with him to Kimberley. In 1935 Peter began studies at the University of Alberta, where he earned a bachelor’s degree and then a law degree in 1942.

from top left: Dee Dee, Ted and Helen; Ted and Helen; Helen with baby; Helen on visit to Mexico in 1950s; Helen and Eve in the Stanley Street home in Nelson. (McBride Collection)

After graduation he enlisted in the Royal Canadian Navy and trained at HMS Royal Roads on Vancouver Island. In the war Lieut. Peter Dewdney served as an officer and commander of Fairmile motor launches in anti-U-Boat operations off Canada`s east coast.

Helen with Dee Dee, granddaughter Eve and a visitor at the McBride cabin and beach at Queen`s Bay, near Balfour (McBride Collection)

Dee Dee earned a bachelor of arts degree at UBC and then a professional librarian certificate at the University of Toronto. In 1944 Peter married Maxine Forbes-Roberts of St. John`s, Newfoundland, and in 1948 Dee Dee married Nelson lawyer Leigh McBride, who had served as a major in the Seaforth Highlander regiment of the Canadian Army in the Allied invasions of Sicily and Italy.

After Ted Dewdney`s death in 1952, Helen came to live with her daughter Dee Dee McBride`s family. Helen moved with the McBrides to nearby Trail in 1969 when Leigh began working in the law department of Cominco Ltd.

Helen with Leigh and Sam at University of Oregon graduation, 1973; Helen; Eve, Maxine, Helen and Dee Dee; Helen and Leigh with Sam and Eve; Helen in Las Vegas in early 1970s (McBride Collection)

Helen had several bouts with cancer in her last decade, and died in Trail November 27, 1976.