Photo collage above: clockwise, from top left — Col. John Hamilton Gray, c. 1860; sisters Margaret Gray (sitting) and Florence Gray, with cousin Edward Jarvis at left, in 1868; and lower photo is their elder sister Harriet Gray, dated 1864. (McBride Collection)

by Sam McBride

The following documents are transcriptions of handwritten letters or notes about the Peters and Gray ancestors going back to the 1700’s. Some are first-person accounts and other documents are copies (in handwriting) of correspondence among cousins.

#1 – Notes on the Gray ancestors by Florence Gray Poole

This letter, written in about 1919 by Bertha’s older sister Florence for her children, has interesting information about 1) John Hamilton Gray’s grandfather George Burns; 2) Gray’s grandmother Mary Stukeley’s family in England; 3) Gray’s mother Mary and his brothers and sisters; 4) Gray’s experience in the British military, including service in India and South Africa; 5) Gray’s attitude towards politics on Prince Edward Island

This is the first page of the Florence Poole document, as copied in her sister Bertha Gray Peters' handwriting.

My grandfather Robert Gray, who had raised and commanded a Regiment for the King in the American War of Independence, married, in Prince Edward Island, when about 60 years of age, Mary Burns, daughter of Major Burns. Of the Burns family I know absolutely nothing, except that my great-grandfather (Major Burns) was on the Guard of Honour of the Coronation of George the Third, and that he and other officers who formed the Guard were given large grants of land in the North American colonies, his share being the north shore of P.E.I.

My father used to say that he (Burns) had been a very “fast man about town”, and I know he had been a “four bottle man”, and my father and his brother blamed his ability to dispose of unlimited port for their inheritance of gout. Major Burns’ wife, my great-grandmother, was nee Stukeley. She belonged to a very old family in Huntingtonshire, where the places Stukeley Magna and Stukeley Parva took their names from the family. Her marriage to Major Burns was a romantic one. She met him when she was on a visit to Bath, and was persuaded by him to a runaway marriage. She and her sister were co-heiresses to their mother, and each had what was then looked upon as a large fortune.

Major Burns laid out some of the money in fitting out a ship with a Lancar crew (probably bought slaves) and took them out to work on his property in Prince Edward Island. The descendants of the Lancars lived for many years in what was called “The Bog” in Charlottetown. I have an original letter from Squire Adelard Stukeley of Stukeley House (my great-great-grandfather) written to his daughter Mary (“Molly”) at Bath, complaining of her not writing to him. He mentioned her “brothers” – I believe they were both soldiers who were subsequently lost off the coast of South Africa in a troop ship. I also have a miniature, found in this letter, which is supposed (from the dress and date) to be a likeness of Squire A. Stukeley (Bishop Courtey pronounced it to be a “Cosway”).

Then too I have a letter from my great-grandmother to her daughter Mary Burns, afterwards Mrs. Gray. I am sorry I cannot send you copies of these letters, but unfortunately they are stored with all our furniture, but when we get access to these letters I will have them copied for you, and will send you a copy of the miniature. My sister in law Miss Poole met a Mr. Prentice whose mother was a Stukeley. He was interested in hearing of Adelard’s daughter, and said that her sister married an Orme of Yorkshire, and that her descendants are living there. He also said the Stukeley pedigree, of which he had a copy, dated from the 12th century, and he very kindly sent me a drawing of the Stukeley coat of arms. I tried to get a copy of the pedigree, but my sister in law had met Mr. Prentice at a County Archaelogical Society, and he did not turn up at their next meeting. I have his letter to her, with the information I have given you; it is stored with the rest of my papers.

My father’s mother died young, leaving two sons and three daughters — the eldest, Uncle Robert, lived nearly all his life in London. He managed the Worral and Fanning Estates. He died unmarried at age 94. One daughter, Aunt Elizabeth, married in P.E.I. Chief Justice Jarvis and left one son, who died unmarried. Another daughter married a W. Cambridge (uncle of my stepmother) and had several children, all dead. Aunt Stukeley lived in Ebury Street in London and died unmarried.

My father was sent to England very young as his father had been promised a commission for him. I suppose the Stukeleys had forgiven his grandmother’s runaway marriage, as he stopped often at Stukeley House. I remember his telling me he was taken to see an aged nurse who welcomed him as “Miss Molly’s boy”. For a few months my father was in a Hussar regiment (18th I think) and there was a cornet in the 7th Dragoon guards, and was nearly 20 years a captain in that regiment. Promotion in those days was by purchase, and as many of the men were rich it was unusually slow. My father married when very young a Mrs. Chamier, sister of Sir William Sewell. She died shortly after their marriage, and he was a widower many years until he met my mother, a young girl of 17, in India, she was just out from school.

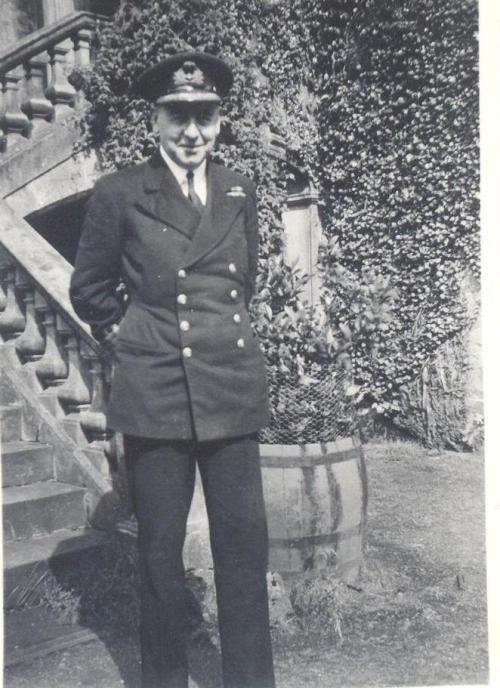

Florence Gray with her grandmother, Lady Pennefather (Margaret Carr Bartley) - McBride Collection

My grandmother (Pennefather) used to tell me that my father was a very distinguished man, and his entertainments etc. much talked about in the Cantonment. The men in the regiment were a very smart set. My father’s principal friend was Capt. Bentund (father of the present Duke of Portland). Sir George Walker and Sir Harry Darrel were also great friends, and many tales were told of their joint escapades. The only one of my father’s brother officers who came to Canada was Gen. Sir Graham Montgomery-Moore, who commanded in Halifax. I knew him well there, and he liked talking of the old days in the 7th D.G. He told me that when as a young Cornet he stood before his Captain, he thought him the realization of his idea of a soldier! Capt. Hamilton Gray was a “splendid figure”, he said. He also told me my father fought a sensational duel and “winged his man”. In those days dueling was encouraged, and every man who joined a crack corps like the “Black Horse” was given a pair of dueling pistols to uphold the honour of the regiment. Soon after my father’s marriage the regiment was ordered out to South Africa, and my eldest sister was born in a troop ship in the Red Sea!

Photograph of Sir Harry Darrel's depiction of the action in South Africa where Col. John Hamilton Gray led a charge of mounted policemen against a gun emplacement.

The first Boer War was going on then, and my father performed an act of gallantry which would in these days have won a Victoria Cross. The general described it to me. The regiment was drawn up in line in a place surrounded by Kopjes, concealed Burghers were potting them on all sides, and a machine gun in a narrow lane was turned on the unlucky cavalry and they were simply mown down, unable to charge or use their sabres. My father took four mounted police men and galloped to the gun, spiked it and cut down the gunners, and two of the police men were killed. Sir Harry Darrel who was an artist painted two pictures of this incident, and for years one hung in the D.G. mess. I have a photo of it, which is fortunate as your Uncle Arthur had the original, and it, with everything else he owned was destroyed in the Halifax explosion during the war.

There was a long period of peace after the war in South Africa, and every one of the wiseacres prophesied that there would never be another war. My father tired of inaction, and having also kept memories of the fine sport in P.E.I., sold out of the service just the year before the Crimean War and went back to P.E.I. A year later when war broke out he was desperate and did his best to get back to his regiment, but he had received ₤9,000 for his Troop, and in those days a man who sold out could not get back in. Then he went on my grandfather Pennefather’s staff hoping to get out to the seat of war, but the “extra” A.D.C.’s had no chance and peace came before he could arrange to enter another regiment. Highly disgusted, he returned finally to P.E.I. where he ended his days. He tried to take an interest in politics, but I don’t think he ever cared for a politician’s life. The only thing that interested him was the Confederation of the Maritime provinces. My mother’s death occurred soon after Confederation and he retired from “The House”.

#2 – A short account of his life by Col. Robert Gray,

King’s American Regiment

This short autobiography by John Hamilton Gray’s father Robert has interesting information about 1) his roots in Scotland, among many Grays near Glasgow, 2) the origin of the “Hamilton” name, in honour of the mentor who helped him get established in business, 3) the loss of his property in Virginia in the Revolutionary War, and 4) details of his arrival as a Loyalist in the Maritimes and how he was rewarded with land and appointments.

As it may afford some satisfaction to my dear children to know something of the early life of their father, I have put in writing the following brief memoirs:

I was born on the 7th Sept. 1747 (old style) in Dunbartonshire, Parish of Kirkentilloch1 in my father’s house, a place rented by him but which had belonged to my ancestors, but sold through reverse of fortune by my grandfather to Robert Gray, a distant relation. My father’s name was Andrew, my mother’s Jean (of the Grays of Lanarkshire, cousins). In a circuit of many miles both in Dunbartonshire and Lanarkshire, many of the principal families were Grays and nearly related to my family by blood or marriage. My father being far from affluent, I was articles for four years to John Hamilton Esq. of Dowan to go to Virginia where his four nephews (sons of Thomas Hamilton of Overton) carried on an extensive mercantile business.

signature of Robert Gray.

The same Thomas Hamilton raised a regiment during the American rebellion (now called the Revolutionary War) and was distinguished for his gallant conduct at the battle of Camden where he was severely wounded. He was afterwards for 22 years His Majesty’s consul for Virginia, and was godfather to my youngest son John Hamilton, and to my deep and undying regret died in London 1816. These gentlemen, the Hamiltons, being anxious to open an establishment in Norfolk, Virginia, I was taken into partnership and for four years carried on a successful business by sea and land, until the breaking out of the American rebellion. Towards the end of the year 1776 all business being at a standstill, Lord Dunsmore the Governor of Virginia, having removed the seat of government from Williamsburg to Norfolk, I entered a corps of volunteers which he was forming to co-operate with His Majesty’s 14th Regt-of-foot in checking the progress of the rebels. In the course of this service I was dangerously wounded, being shot in two places, the rebels having obtained the ascendancy by land. His Majesty’s loyal subjects and the troops embarked on board the shipping in Norfolk Harbour. The Town was soon afterwards burnt to ashes by the damned Rebels, and all the valuable property in our warehouses consumed in the flames or plundered by the enemy. I remained in Virginia with Lord Dunsmore on the fleet carrying on a predatory war against the enemy till the month of July when we sailed for New York where Sir William Howe had arrived with a large army. There I met Col. – now General – Fanning, who being about to raise a regiment for His Majesty, appointed me to command a company and also to be paymaster to the King’s American Regiment. I remained with the Regt in various parts of North America, from Rhode Island to Georgia both inclusive. I was in several actions at the siege of Rhode Island and commanded the Fort-of Goal-Island when it was cannonaded by the French fleet under Count D’Estaing. I was also honoured with the command of Port Georgetown when it was evacuated. At the end of the war 1783 the Regt being reduced I was placed on half pay.

In the autumn of 1783 I arrived inHalifaxand in the following spring was sent with a commission of “Surveyor of Land” to superintend the settlement of the Loyalists in thecounty of Shelburne,Nova Scotia, where I was employed for three years having 13 deputy surveyors under me.

In 1787 I received pressing invitations and flattering promises from Gen. Fanning who had been appointed Governor of Prince Edward Island. I arrived in Charlottetownon the 11th July that year, and was appointed Judge of the Supreme Court – a member of His Majesty’s council and private secretary to Gen. Fanning. In 1790 I went to London by way of Portugal on private affairs and returned at the end of the year. In 1792 I was sent to London with full powers to conduct the defence of Gen. Fanning and other Crown officers against complaints preferred against them and having successfully performed my mission returned in 1793. Next year I had the principal share in raising a corps of men for the defence of theIsland, which I commanded until the Peace of Amiens in August 1792.

#3 – “Relating to my Mother” by Florence Gray Poole

My mother, Susan Ellen Bartley, was an only child. Her father, a Lieut. In the 22nd Regiment, died at a very early age (about the year 1825) when quartered in Jamaica. His widow married Major Pennefather, also of the 22nd Regt, and afterwards General and G.C.B. There was no second family, and Maj. Pennefather treated my mother as his own child. I believe she did not know of the “step” relationship until she married.

Painting of Margaret Carr Bartley c. 1830, around the time of her marriage to Major Sir John Lysaght Pennefather

One of my grandfather’s brothers, Sir Robert Bartley, was a distinguished soldier in the Peninsular War. There is a monument to his memory in some English, or Irish, cathedral or church. I remember a print of it hanging in my mother’s bedroom in Prince Edward Island. I have tried by writing to Notes and Queries to find out where this monument is but without success. The man who answered my question knew all about Robert’s fame and wrote that he died at sea on his way home, but did not know where the monument is. It would be interesting to find it.

The only Bartley relation I ever saw was my “Great Aunt Jessie”. I was taken to see her when a small child in Dublin. It is a pity that my mother did not correspond with this aunt, as I have been told that she lived to a great age, and either not knowing or forgetting that she had four grand-nieces in Prince Edward Island, left her money, or a fair amount I believe to her companion!

One of the Bartleys married a Cowell. Their grandson Major Cowell was Governor to Prince Alfred (the Duke of Edinburgh) and afterwards when Sir John for many years “Controller of the Household” to QueenVictoria. Sir John was with the Duke of Edinburgh when he visited Canada. I remember his coming to see my mother, incidentally bringing the Prince to the great wonderment of the P.E. Islanders. We knew Sir John’s sisters, one married a Major Beadon, but I have never met any of the present generation. One of Sir John’s daughters married Admiral Curzon-Howe. I think I have told you now all I know.

Your great-grandmother’s maiden name was Carr. She and her sister were orphans when very young and were brought up by an uncle at his place inTipperary “Little Island”. Another uncle was named Senior – any of their descendants of whom I have heard were soldiers.

My grandmother’s sister married a Carr cousin. His grandson I have known since we were children. Lt. Col. Lawless R.A.M.C. is the only survivor of a family of cousins. He has interesting miniatures of the Carr family. One (an aunt of my grandmother) has a romantic story. She was a beauty and toast in Dublin…

#4 – Letter from Florence Gray to G.E. Lawless

This letter was written by Bertha’s sister who had taken an interest in the family history. She is corresponding with a distant cousin. The main focus of this letter is the Bartley side of the family. Florence’s maternal grandmother was Margaret Carr, who married Lieut. William Bartley and had a child Susan before he died of illness while serving inJamaicain the 1820’s. Margaret later married William’s commanding officer General Sir John Pennefather and became “Lady Pennefather”. Susan married John Hamilton Gray.

I am afraid I cannot tell you very much about your mother’s people – I wish I had listened more attentively when my grandmother discoursed about her “young days”, for of course during my 30 years in Canada I lost sight of my Irish connections. Our grandmothers, Margaret and Ellen Carr, were sisters; their parents died when they and their brother Richard were young. The girls were brought up by their maternal uncle Morton of “Little Island” Tipperary, Richard being sent to a London Counting house to make his way.

From what my grandmother used to say, I think “Little Island” was a family place of some importance, and the girls went out a great deal. Your grandmother married her first cousin William Carr; my grandmother married Wm. Bartley, Lieut. In the 22nd Regiment and went to Jamaica, where my mother was born and my father died very young. His brother officer Major Pennefather brought my grandmother and her child home, and a year later they were married. My mother was sent to a French convent while her parents were in India. She used to spend her holidays with your grandparents, and she and your mother, both called Susan after their grandmother, were great friends.

Your grandparents were very well off then, and I well remember my mother’s grief when she heard of your grandfather’s loss of fortune and a little later of his death. I do not know the particulars, but remember that my father and mother often spoke of “Uncle William” having been exceptionally honourable. My grandmother often talked of another uncle called Senior, I think he was in the Service. I know some of his sons and grandsons were soldiers.

I only met one first cousin of our grandmothers, a perfectly delightful old lady, Mrs. Fitzgerald. She spent a winter in London when we were in Crawley Place. Her son, or nephew, Capt. Fitzgerald (known to us as Dicky) afterwards commanded the 69th Regiment. I have tried to find him. I think he must be dead. I have a photo of a very good looking Anna Maria Morton, granddaughter of Morton of Little Island. She married a man in the service whose name I forget, and went toIndia, I think she was the last of the Mortons of Little Island.

My grandmother and her husband Gen. Pennefather objected to the “step” connection known. I believe that my mother did not know of it until she married.

Susan Bartley Pennefather Gray

This has been rather hard on us, as we have never been in touch with our grandfather’s relations (with the exception of the Cowels who claimed cousinship), and your sister in law tells me that our grandfather’s youngest sister died a few years ago, leaving a large fortune to her companion as she had “no near relations”. The silence about our grandfather was so marked that I fancied all sorts of things and was relieved when dear George told me that when he first went to Newfoundland 40 years ago he dined with the Governor (whose name he did not remember) and the subject of Jamaica coming up, the Governor told him his dearest friend “young Bartley of the 22nd regiment was buried there, and that he was the nicest fellow he ever knew.

#5 – Letter from Prentice to Miss Ellen Poole March 25, 1899

62 Shrewbury Road,Birkenhead

Dear Miss Poole:

I have read with great interest the notes you have kindly sent me about the Stukeleys and you will be glad to hear that I can give you their pedigree back to about 1150 and a good deal of information about the family.

A.S. Stukeley (Adlard Squier Stukeley) the father of Mary (Mrs. Florence Poole’s great-grandmother) was brother to my progenitrise Margaret Stukeley, so curiously enough Mrs. Poole and I are far away cousins.

The Stukeleys came originally from Great Little Stukeley in County Huntington and one of the family about 350 years ago marrying the heiress of the Fleets of Fleet in County Lincoln settled at Holbeach, close to where they owned considerable estates, their residence was at Stukeley house, where my mother was often resident with her grandmother Mrs. Sturton (her husband was Private Secretary to the Marquis of Rockingham when Prime Minister and first cousin of Mary Stukeley) and my cousins the Stukeleys still live at Holbeach. The Stukeley house has, I am sorry to say, changed hands. Dr. William Stukeley the famous antiquarian was of the Holbeach branch and was born there.

It has always been a mystery to us what became of the other Stukeleys after leaving Holbeach, as they were supposed to be fairly well off and they seemed to have suddenly disappeared, the information contained in Mrs. Poole’s notes evidently solves the mystery.

Mary Stukeley’s (baptized at Holbeach 13 March 1744) sister Sarah married Walden Orme of Peterborough and left issue, something about them I might be able to trace.

There is a splendid old church at Holbeach where most of the Stukeleys were buried, and in it remain some of their monumental inscriptions. I was there about 4 years ago.

As I think Mary and Sarah Stukeley were the only surviving issue (of a large family) and eventually co-heiresses of Adlard Squier Stukeley they would carry the arms of Stukeley quartering Fleet in to their husbands’ families. …it is just possible therefore that failing surviving male issue of the Burns and Gray being the descendants of Mary, your brother’s (he means Henry Poole) children may be entitled to quarter these arms with those ofPoole.

#6 – Helen Dewdney’s family history notes c. 1950’s

Judge Peters was my grandfather. He died when I was three years old but I remember him perfectly. He seemed to always be in bed. A fine-looking man with quantities of white hair.

Helen Peters in about 1895 in Charlottetown when her father Frederick Peters was premier of Prince Edward Island.

His youngest daughter Maggie – who adored him – was always fussing over him. The old doctor was generally in attendance, but Maggie insisted on another opinion. He was 85 – had Aunt Maggie never heard of old age? …The judge was very fond of his dogs. He had three of them. One bit a grandchild and Aunt Janie was upset and said “the dog must be shot!”. “What!”, cried the judge, “if any shooting is to be done, it won’t be a dog.” So nothing was shot. But I think he must have been pretty nice.

He was very fond of his daughter Carry (Caroline), and when she was going to marry a Bayfield he thought it would be a kind gesture to have the wedding in the Bayfield Church. It was Anglican as was the Peters’ church, but very “low” whereas St. Peters was very “high”

#7 – Notes of Helen Dewdney c. 1970

She was apparently writing on note paper while waiting in a doctor’s office. She had just read a book called “My First Hundred Years” (not sure of the author or date of publication, but it would be some time before she died in November 1976)

“…She called her Father ‘Papa’ and her mother ‘Mamma” just as my mother did, except my mother always referred to her mother as ‘my dear little Mamma”. Dear little momma, my grandmother, lived in London with her father and mother in one of those old-fashioned London houses.

Her father was General Sir John Pennyfeather. She was the only child. I have her picture painted by a wonderful artist. Only 16, a beautiful face, with dark curtains of hair on each side making her look about 30. At 16 John Hamilton Gray met her and married her. He was much older than she and an officer in the army.

He took her to various places, and she had a baby in so many different places. I don’t think there was one born where another was. First there was my aunt Harriet. Later my great-grandmother Lady Pennyfeather adopted aunt Harriet and left her everything she had. Lady P lived till she was 98. Her eyesight and hearing were perfect, but she did admit the stairs tired her a little. Aunt Harriet married when she was older. I never did know what age. When I was young it wasn’t considered quite nice. I never knew my mother’s. In any case she died a few months after Great-grandma, and everything went to the husband as the child died too. So we don’t have many mementos of Great-grandma. Well, anyway, after Aunt Harriet came Aunt Margaret who lived and died in Charlottetown– much loved and living until she was 98.

Then came Aunt Florence who married Henry Poole a mining engineer. Six children they had – three boys and three girls. I remember staying with them once when I was 7 or 8 along with Fritz my brother (who was) 2 years younger. He cried so much they were obliged to send him home to theIsland(P.E.Island) where we lived. I remember feeling it a pity he had no bravery. Funny isn’t it… he lost his life and received the V.C. in Oran in Africa, his seventh decoration. No bravery, eh.

Uncle Henry Poole was 6 ft 3 inches or so tall and had a beard and moustache. I was simply terrified of him. He was a very honorable man and brought up his six children with a very high sense of honour. He was a very good father. If he loved one more than another it was Edward, who was brilliantly clever. He passed first in Kingston, became a mining engineer and went up to some lovely spot up north where almost immediately he contracted typhoid and died very quickly. A young man he scarcely knew happened to be there. “Stay with me,” said Edward, “till it’s over”. It seemed so sad – so young, and he must have put so much effort in being first and all. Just seems like wasted. Uncle Henry was walking along in a railway station and he received this telegram: “your son is dead, what shall we do with remains?” He fell in a dead faint.

Edward’s twin sister Dorothy was beautiful, not just pretty. I knew her when she was 19. She stayed with us in Victoria. Great dark eyes and hair reddy brown wavy luxuriant. Lucy her sister was rather plain, but if there was a crowd anywhere laughing and talking vociferously, you’d know Lucy would be in the middle. Uncle Henry would say “The men come for Dorothy but stay for Lucy.”

After Florence, John Hamilton Gray and Susan Pennyfeather had two more daughters: Mim (who married Abbott) and Mother.

The Pooles for a while lived in Stellerton, a mining town in the East. They also had a son Ray who had a son and daughter; Evelyn who died; Dorothy who died; Eric who died; Edward who died. Lucy married a man called Kenneway who was quite well off and in later years became stone deaf from the guns in a war. Someone once asked me which war was it, the first or second? I said it was the Boer War … I forget I am so old. The Kenneways had a son who was killed in war and a girl Monica.

…The judge (James Horsfield Peters, father of Frederick) must have been a dear, but quite an autocrat around the home and I think at times he bore down on Sarah the cook a bit. Sarah would sniff and say she’d better be leaving , she couldn’t stay in a place where she didn’t give satisfaction. I am sure she never would have left. She loved Grandmama and Grandmama would slip a five dollar bill in her hand. “Oh Sarah, pay no attention to the judge. You know how he is. He’s just like that. He’ll get over it.” And Sarah allowed herself to be comforted by just about the sweetest person who ever lived – Mary Peters, born Mary Cunard. Granted the five dollars came easily (her father Sir Samuel Cunard died a millionaire), but the sweet and lovely way she did it to Sarah was her own. When she died, she died in Sarah’s arms. You can see in her photograph that she was overweight and probably no exercise – in those days they just didn’t know…

My mother used to love going over to the Peters house. It was so different from her own. There were always 3 puddings on the table, because Fred was so fond of one thing, and Uncle Spruce and Uncle Thom could not be without their so and so.

…The Mellish family was in Hodsock Priory, Worksop, Nottinghamshire. There was Henry Mellish, Agnes Mellish and Evy Mellish. The last I heard of the place it was empty. So sad. I always thought Cousin Aggie was so pretty. They were Father’s relations – Cunards