Here is a list of postings on thebravestcanadian.wordpress.com blog since it started in December 2011. These postings can be accessed through the Archives list on the right side of the screen. To view the Archives listing of months, click on the About tab.

December 2011

Biography of Fritz Peters, VC to be published in 2012 – Dec. 8, 2011

Ancestry of Frederic Thornton Peters, VC – Dec. 12, 2011

Fritz Peters’ first medal was for rescue actions following Messina earthquake – Dec. 15, 2011

Hilarious BBC broadcast of 1937 fleet review by inebriated Lt.-Cmdr Woodrooffe – Dec. 16, 2011

Naming of Mount Peters near Nelson, B.C. after Canadian war hero Fritz Peters, VC – Dec. 19, 2011

Proper spelling is “Frederic Thornton Peters”, NOT “Frederick” – Dec. 21, 2011

Souvenirs from the Victoria Cross Centenary of 1956 – Dec. 22, 2011

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part One: his father, the Hon. Frederick Peters, QC – Dec. 25, 2011

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Two: his mother, Roberta “Bertha” Hamilton Susan Gray, Daughter of Confederation – Dec. 25, 2011

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Three: his sister, Helen Dewdney – Dec. 26, 2011

January 2012

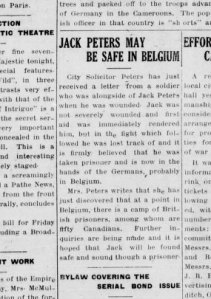

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Four: his brother, John Francklyn “Jack” Peters – Jan. 2, 2012

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Five: his brother, Gerald Hamilton Peters – Jan. 5, 2012

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Six: his brother, Noel Quintan Peters – Jan. 6, 2012

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Seven: his sister, Violet Avis Peters – Jan. 8, 2012

February 2012

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Eight: his four grandparents – Feb. 7, 2012

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Nine: his cousins – Feb. 21, 2012

March 2012

Peters Family Papers: family history documents – March 10, 2012

New book “The Bravest Canadian” tells the story of Capt. Frederic Thornton “Fritz” Peters, VC – March 17, 2012

Letters from Private J.F. “Jack” Peters, Part One: Dec. 1914 – February 1915 – March 24, 2012

1914 Christmas card from Lieut. Frederic Thornton Peters on HMS Meteor – March 28, 2012

April 2012

Letters from Lt. Gerald Hamilton Peters, Part One: 1915 – April 2012

Letters from Lt. Gerald Hamilton Peters, Part Two: 1916 – April 2012

Implications of the sinking of Titanic in the Fritz Peters story – April 18, 2012

Itinerary for Helen Peters Dewdney and other Canadians at the VC Centenary in England in 1956 – Apr. 20, 2012

May 2012

Family of Frederic Thornton Peters – Part Ten: his brother-in-law Ted Dewdney – May 6, 2012

June 2012

Letters from Frtiz`s Brother Jack Peters, Part Two: March 11, 1915-April 13, 1915 – June 30, 2012

August 2012

Fritz Peters cadet report in 1906 – August 18, 2012

Scandal of first wife of Dr. Charles Peters and a pirate in New York in early 1700s — August 27, 2012

Condolence letters received by Bertha Gray Peters in 1916 — August 30, 2012

September 2012

Biography of Canadian War Hero Fritz Peters, VC – September 8, 2012

October 2012

Letters reveal Fritz Peters` way of thinking and love of literature — October 19, 2012

November 2012

New information emerges on the air crash that killed Fritz Peters 70 years ago today — November 14, 2012

Author interviewed on Montreal-based The Stuph Files — November 16, 2012

“The Bravest Canadian“ now available in bookstores and online — November 17, 2012

Front cover image of book — November 18, 2012

Back cover image of book – November 18, 2012

“The Bravest Canadian“ selling well in B.C. and P.E.I. — November 18, 2012

Telling the Fritz Peters story at the Royal British Columbia Museum — November 21, 2012

Author`s presentation on Fritz Peters Nov. 10th at Royal B.C. Museum — November 21, 2012

Feature on Fritz Peters book in Victoria`s Monday Magazine — November 24, 2012

70 years ago General Eisenhower awarded Fritz with U.S. DSC medal — November 28, 2012

December 2012

Book launch event Dec. 15th at Touchstones in Nelson — December 5, 2012

“The Bravest Canadian“ launched at Touchstones Museum — December 17, 2012

Nelson Star article on `The Bravest Canadian – Fritz Peters, VC“ — December 18, 2012

Memorable quotes of Frederic Thornton Peters — December 18, 2012

January 2013

Memorable descriptions of Frederic Thornton “Fritz“ Peters — January 17, 2013

Daughter of lifelong friend Cromwell Varley has fond memories of Fritz Peters – January 18, 2013

February 2013

Genealogy event in Castlegar, B.C. on Feb.11, 2013 — February 4, 2013

“The Bravest Canadian“ reviewed in Naval Association of Canada`s Starshell magazine — February 9, 2013

P.E.I. Heritage Award and book signings in Charlottetown — February 10, 2013

Presentation on The Bravest Canadian – Fritz Peters VC` on Feb. 23rd at Hotel on Pownall — February 16, 2013

Busy in heritage-minded Charlottetown — February 22, 2013

Interview with author can be seen on CBC Charlottetown TV web link — February 22, 2013

Exploring Fritz Peters sites in Charlottetown — February 28, 2013

Fritz Peters book recognized with P.E.I. heritage award — February 28, 2013

April 2013

70 years since official announcement of F.T. Peters` Victoria Cross — April 18, 2013

Estate of Fritz Peters valued at 254 pounds — April 27, 2013

May 2013

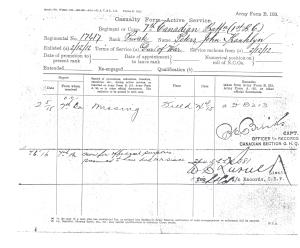

Pte. John Francklyn Peters (1892-1915 — May 5, 2013