by Sam McBride

In his letters home, Frederic Thornton “Fritz” Peters often had kind words for his brother-in-law, Edgar Edwin “Ted” Dewdney (1880-1952), who married his sister Mary Helen (known by friends and family as “Helen”) Peters in June 1912.

Fritz may have met Ted soon after the Peters family arrived in Victoria in 1898, as Fritz’s father Frederick Peters and Ted’s uncle and guardian, the Hon. Edgar Dewdney, were friends and business associates. Ted was nine years older than Fritz, and would soon begin a lifelong career with the Bank of Montreal. It is likely that Fritz encountered Ted most often in the period after Fritz returned to B.C. following retirement from the Royal Navy in June 1913, until Fritz re-enlisted at the outbreak of war in August 1914.

In a 1917 letter, Fritz said he was glad that Helen married a Canadian rather than an Englishman “because I am a tremendous believer in country.”

It must have been very difficult for Ted to go through the First World War on the homefront rather than serving in the army. At 33, he was past the ideal age for a soldier, but it is extremely likely that he would have signed up if he was a bachelor, as he was fit, athletic and had substantial militia training. But for him to serve, his wife would have to give her approval in writing, which she was unlikely to do, as she and her one-year-old daughter Eve Dewdney were Ted’s dependents. Helen was never keen on the war as a young woman, and she likely felt her family was doing more than its fair share for the war with four brothers in service – Fritz in the Royal Navy, Jack and Gerald in army battalions of the Canadian Expeditionary Force, and later Noel in the Canadian Forestry Corps.

Helen would not support Ted enlisting

Helen was devastated after Jack died in the Second Battle of Ypres in April 1915 then Gerald died in the Battle of Mount Sorrel in June 1916. News of the deaths of the two brothers came within a few weeks of each other, because Jack was incorrectly believed to be a prisoner of war until May 1915. While Helen was discreet in not expressing controversial opinions in public, she was decidedly anti-war for the rest of her life. Like many next-of-kin who lost loved ones in the First World War, she harboured resentment against generals, and felt they could not be trusted. Referring to the previous president, Dwight D. Eisenhower, in the 1960s she said to me “the Americans should never have allowed a general to be president.”

Ted’s father served in the British cavalry

As a boy, Ted was keen on army service because his father Walter Dewdney served for 12 years in the 17th Lancers cavalry regiment of the British Army. The birth records are not conclusive, but it appears that Walter was born in 1836 in Devonshire, and joined the army in 1854 at age 18. He may have fudged his birth year in his enlistment, to make himself old enough for service. He had a rollercoaster-like experience in the British military, rising quickly from private to troop sergeant-major, and then was busted back to private by the time he retired from army service in 1866.

Walter joined the Lancers in the spring of 1854, and came close to being in the famous Charge of the Light Brigade in Balaclava in the Crimean War, on October 25, 1954. The Light Brigade consisted of the 17th Lancers, as well as the 4th and 13th Light Dragoons and the 8th and 11th Hussars. Of the 147 men of the 17th in the charge, just 38 were at the roll call the following morning. The charge was celebrated as a demonstration of British courage in the poem of the same name by Lord Alfred Tennyson, though the folly of the near-suicidal charge was noted in the poem in the line “someone had blunder’d”. The Lancers suffered 45 per cent casualties in the charge, which resulted in a position in the unit being available for Private Walter Dewdney. It is likely that Walter heard many first-hand accounts from comrades-in-arms who survived the charge and continued with the Lancers.

As a boy, Ted learned from his father Walter how to ride a horse like a cavalryman. It is likely he also heard stories from his father’s army service, which included the Indian Mutiny, in which Walter won the India Mutiny Medal, as well as the Crimean War. Walter came to British Columbia in 1866 after retiring from army service with an honourable discharge.

The family connection with the Charge of the Light Brigade is interesting because of similarities between it and the attack on Oran Harbour on November 8, 1942 under the command of Captain Fritz Peters. A war correspondent noted that a number of men on HMS Walney recited lines from the poem after they learned of the extreme danger of their mission after leaving the rendezvous point of Gibraltar towards Algeria. There were several similarities between the 1854 charge and the 1942 charge through the Oran Harbour boom. Both charges had a force of approximately 600 – referred to in the poem as the “noble 600”. Oran harbour was about a mile and a half in length – about “half a league” in the old form of measurement stated in the first line of Tennyson’s verse. Both charges came about as a result of miscommunication among commanders, and both suffered massive casualties while failing to achieve their objective.

Walter came to sad end

As was common with soldiers of that era, Walter suffered from illness during much of his service. Among other ailments, he had malaria and sunstroke. There is no record of him being wounded in action. He participated in a particularly long and rigorous battle march in the India Mutiny campaign. After retiring from the army in 1866 Walter came to Canada, encouraged by his brother Edgar who had arrived in British Columbia in 1859 and made a name for himself as a civil engineer, trail-builder and politician.

Walter had some success as a prospector in the Cariboo region, and had mining-related appointments in Victoria, Yale and Vernon. His friends from growing up in England and army service included the novelist Robert Louis Stevenson, who visited Walter and his family in Victoria.

Acquaintances said Walter never completely recovered from the malaria he army service abroad. He also suffered excruciating pain from injuries suffered in the Cariboo when pranksters put tacks under his horse’s saddle. When Walter jumped on his horse with the confidence of a cavalry veteran, the pain from the tacks caused the horse to throw him off, resulting in head and body injuries that could not be treated by the medicine of the era.

Ted’s maternal grandfather, William Leigh, who served as Victoria’s City Clerk for 20 years before his death in 1884.

His first wife (Ted’s mother) was Caroline Leigh, daughter of William Leigh, city clerk for Victoria. Carrie died in childbirth in 1885 when Ted was four years of age. A couple of years later Walter married Clara Chipp as his second wife. Ongoing physical pain, along with some bad financial news from England, led Walter to commit suicide on January 28, 1892. He shot himself in the head while sitting at the desk in his office in the family home where he did his work as gold commissioner. The Victoria Colonist newspaper reported that the first person on the scene after the shooting was his son Ted, age 11 at the time. It must have been traumatic for Ted, because for the rest of his life, he never talked of the shooting, except to his wife Helen. The only information his children had of the suicide came from their mother.

After their father’s death, Ted and his brother Walter Robert Dewdney and sister Rose Dewdney went to live with friends of the family, including the sister of Rev. Henry Irwin, a popular figure in B.C. history known in the frontier communities as “Father Pat”. After a few months of temporary stays in the North Okanagan area, the children went to Victoria to live on a permanent basis with their uncle Edgar Dewdney and his wife Jane. As they arrived, Edgar was beginning a five-year term as Lieutenant-Governor of B.C. and living at the vice-regal estate known as Cary Castle. In 1893 Edgar became Ted’s legal guardian. Because both uncle and nephew had Edgar as their first name, within the family the uncle was known as “Ned” and the nephew as “Ted”. Jane also had a nickname, as she was known as “Jeannie”.

As a boy, Ted was a keen student of history and literature and wanted to study at McGill University in Montreal, but his uncle Edgar, who was his legal guardian, insisted that Ted go to work in business at an early age. Ted was a couple of months shy of 17 when he began with the Bank of Montreal as a teller in Victoria. He was transferred to bank branches in New Westminster and Greenwood, and then in 1900 began as a clerk with the Bank of Montreal in West Kootenay gold-mining town of Rossland, B.C. Later that year, his stepmother Clara, who had married William Cameron after Walter’s death, contracted cancer. Experiencing extreme pain from the cancer, Clara killed herself by drinking carbolic acid, a common way of committing suicide by women of her era.

Soon after arriving in Rossland, Ted joined the local branch of the Rocky Mountain Rangers (RMR) militia. In the next seven years Ted would make many friends in Rossland and rise from private to lieutenant in the RMR. When the bank transferred him to the Okanagan community of Armstrong in 1907, his friends in Rossland – particularly comrades in the RMR – honoured him with a high-profile farewell party at the Rossland Club, which was the young city’s white-collar social and business club of the time.

The Bank of Montreal transferred Ted to Victoria, where he courted Helen Peters, and then back to Rossland. Ted and Helen married at the St. Paul’s Anglican Church in Esquimalt in June 1912, and went to live in Vernon, where Ted was beginning a new assignment as accountant of the local bank branch. Their first child, daughter Eve Dewdney, was born in December 1913, and then in the spring of 1915 Ted moved to Greenwood to begin his first appointment as branch manager. A year later, the Dewdney family moved to the silver-mining community New Denver, where they lived in quarters above the bank office managed by Ted, which today serves as New Denver’s Silvery Slocan Museum.

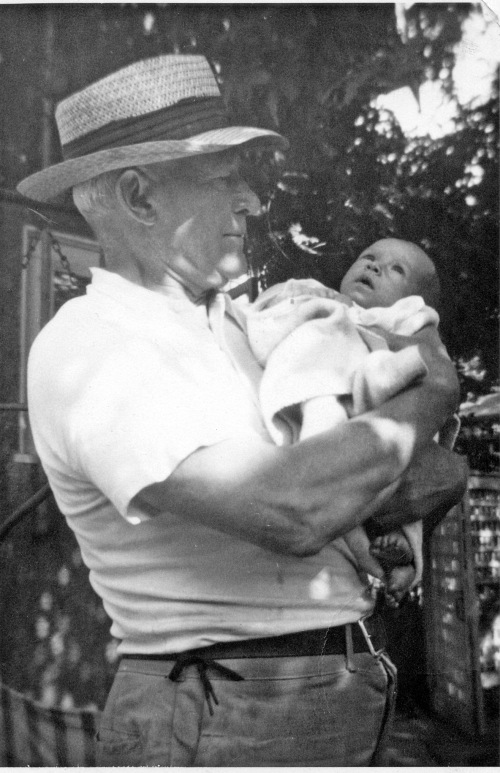

While at New Denver, Helen learned of the deaths of her brothers Jack Peters and Gerald Peters in the war. Her despairing mother, Bertha Gray Peters, came to live with her daughter’s Dewdney family after returning from England, where she was staying during the war years to be close to her sons in battle. In May 1917, Ted and Helen’s son Frederic Hamilton Bruce Dewdney was born. As a toddler, he picked up the nickname of “Peter”, and was known as “Peter Dewdney” the rest of his life.

In 1920 the family moved to Rossland in line with Ted’s transfer to manage the Rossland branch. Daughter Rose Pamela Dewdney – who went by the nickname “Dee Dee” from an early age – was born in 1924. Ted transferred to manage the nearby Trail branch in 1927, and then was moved to Nelson in 1929, retiring there in 1940 after 42 years with the Bank of Montreal. Helen’s mother Bertha stayed with the family through every move, and helped with meals and looking after the children. She was in good health until suffering a serious fall down the stairs of the Nelson house in about 1935. The fall left her disabled and bedridden for the rest of her life. Upon Ted’s retirement, the family moved from the Nelson Bank House known as “Hochelaga” to a heritage house he purchased on Stanley Street.

As a young man, Ted was athletic and a champion tennis player, winning the West Kootenay Tennis Singles event three years in a row. He was also a keen fisherman, rower and stage manager for his wife’s musical and theatrical productions. He was also extremely active in community groups and charities, including the Anglican Church, the Red Cross, the Kootenay Lake Hospital board, and the Welcome Home Committee that assisted veterans returning from service abroad.

Ted died at age 71 in 1952 from a heart condition which today might be remedied by bypass surgery. His widow Helen inherited his Dewdney memorabilia and went to live with her daughter Dee Dee McBride’s family. In 1968 the Dewdney Papers that Edgar left to his nephew Teddy in his will were donated by the family to the Glenbow Archives in Calgary. As they include extensive correspondence between Edgar Dewdney and Prime Minister John A. Macdonald around the time of the Northwest Rebellion of 1885, the Dewdney Papers are often accessed by researchers and writers of Canadian history.