By Sam McBride

My father Leigh Morgan McBride (1917-1995) enlisted for Canadian military service in 1941 immediately after graduating in law from the University of Alberta but before his bar examination, the last step before qualifying as a lawyer. With his maturity, education and achievements, he was taken on for officer training, including time at Gordon Head near Victoria, B.C. and Currie Barracks in Calgary, Alberta.

Leigh M. McBride and his brother Kenneth G. McBride, both proud to be officers of the Seaforth Highlanders of Canada. Family photo.

As a lieutenant, he led his Seaforth Highlanders of Canada unit ashore in the Allied landings at Pachino in the southwest tip of Sicily. It was the largest amphibious invasion in history, and destined to be exceeding size a year later with the D-day invasion of the French coast. The invasion could have been a bloodbath like Dieppe the previous summer, but at that point Italians were turning away from Mussolini, and as a result surrendered in large numbers to the Allies. The situation changed dramatically when Germany sent some of its best troops to stop the Allied advance. Leigh was in the thick of the fighting against the Germans until being hit in the shoulder by a bullet. He later said he was fortunate that the bullet did not hit any bones in his shoulder, but the wound must have been substantial, as he was sent to an Allied hospital in North Africa via Malta for treatment. He returned to his regiment in November, and was in at the forefront of the Allied advance to Ortona, which would be one of the bloodiest battles of the war, commonly known as “little Stalingrad” after the gigantic victory of the Russians over their German attackers by the Volga River. I remember Leigh often talking about the extraordinary Christmas dinner that the Seaforths enjoyed in a church in Ortona. As per military tradition, on Christmas he and other officers were the waters and servers of the privates, corporals and sergeants. Thirty years later, in April 1975, he visited the re-built church with Seaforth buddies who were at the famous dinner, including the quartermaster Borden Cameron of Vancouver who organized the food and drink for that event which went on just a few blocks from where vicious street-fighting was going on between the two sides.

Leigh met a fellow Nelsonite while in North Africa for treatment of a bullet wound to his shoulder. Nelson Daily News

The hilly terrain in Sicily and mainland Italy was such that the advantage was almost always with the defending forces. On May 23, 1944 Leigh and his men were part of an ambitious attack on the Hitler Line. That day is remembered as his hometown city of Nelson’s Black Day of the War, as two Nelson boys (Priv. Ray Hall and Priv. Jack Wilson) were killed, and two others (Leigh and Priv. Joe “Bud” Dyck) went missing. Both were seriously wounded and were hospitalized at Italian and later German hospitals. Word came through the International Red Cross in July that Bud was alive and recovering in a German POW camp, but it was not until September 20, 1944 – four months after going missing – that his parents were advised that he was alive in a German POW camp, recovering from serious wounds, including schrapnel to his legs, arms and face, and the permanent loss of his left eye. In response to a request for the Regimental History of the Seaforth Highlanders, Leigh wrote about the fateful day he was captured (see the November 4, 2019 posting in this blog).

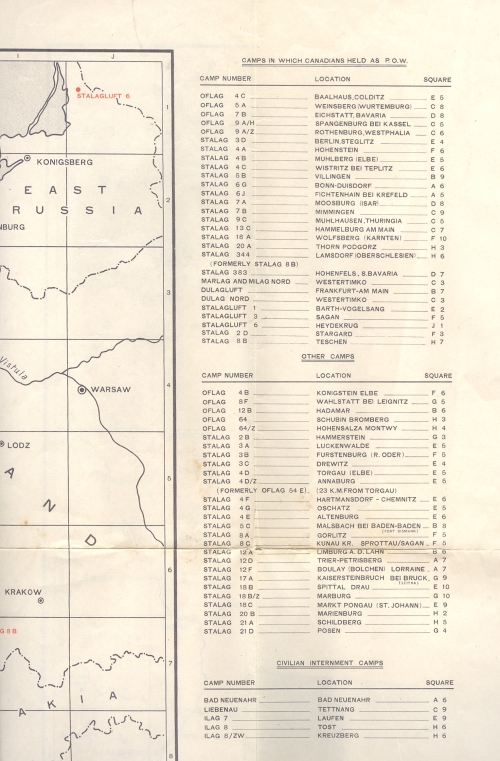

Leigh received treatment at a hospital in Rome before being sent by train for medical care in Germany, followed by time in prisoner of war camps. I am not sure how many POW camps he went to, but once when I visited Regensberg as part of Western Europe he said “oh, I was in a prison in Regensberg”. His last camp before repatriation was Oflag 7B (VIIB) north of Munich. This was a camp for Allied officers. He describes his experiences at this camp and others in newspaper interviews conducts as he was returning home in February 1945, and later in presentations in Nelson in March and April 1945.

Leigh received treatment at a hospital in Rome before being sent by train for medical care in Germany, followed by time in prisoner of war camps. I am not sure how many POW camps he went to, but once when I visited Regensberg as part of Western Europe he said “oh, I was in a prison in Regensberg”. His last camp before repatriation was Oflag 7B (VIIB) north of Munich. This was a camp for Allied officers. He describes his experiences at this camp and others in newspaper interviews conducts as he was returning home in February 1945, and later in presentations in Nelson in March and April 1945.

He knew as early as October 1944 that the extent of his wounds made him a good candidate for a prisoner exchange and repatriation. His parents worked tirelessly to get packages of supplies, particularly food, to him through the Red Cross, which was trusted by the Germans.

His repatriation was confirmed on about January 11, 1945 when he was at the German military centre Heilig Annaburg near Berlin, where he was photographed in a group with other injured Allied officers about to head home in prisoner exchanges.

My dad rarely went to movies, but he did make a point of taking our family to a drive-in theatre in Spokane, Washington in 1970 to see the movie “Patton”, where much of the story involved the Allied push across Siciliy and the conflicting egos of American General Patton and British General Montgomery. I suspected his Seaforth Highlander friends recommended the move, and he told me it was very well done. I don’t think he ever saw the movie “The Great Escape”, and I never heard comments about it from him one way or the other. That escape concluded in May 1944 just a couple of weeks before he was captured. Hitler’s vengeful act of having 50 of the escapers shot would have been one more reason for the next-of-kin of POWs to be worried about getting them back.

In retrospect, they had good reason to worry. On April 14, 1945 a group of British and Commonwealth officers was being marched away from the camp when they were attacked by an American warplane which mistook them for German troops. Fourteen of the POW officers were killed and 46 wounded. The camp was liberated by the U.S. Army two days later.

Leigh’s mail card from Oflag 7B POW camp. It may have arrived in Nelson after he was home.

Leigh occasionally watched the TV comedy “Hogan’s Heroes” and enjoyed it. He said while in one POW camp he played chess with a German guard who looked a bit like Sgt. Schultz in the show. Through the efforts of his parents, Leigh was able to get law books included in his Red Cross packages which he read in preparation for the bar exam he would be taking after returning from the war.

German Christmas card image from Oflag 7B

After his prisoner exchange was confirmed, he left Heilig Annaburg by train for the Swiss border. As a result of Allied bombing, rail trips took about four times longer than normal. He became officially free in Constance, Switzerland. From there he was taken to the port of Marseilles, which had been liberated in the Allied invasion of southern France in the fall of 1944. The Red Cross ship “Gripsholm” took him to New York, where he and other freed Canadian were taken in a sealed railway car to Toronto, and headed west from there on the Canadian Pacific Railway. Reporters met them at several locations along the way, but, as part of the repatriation agreement, they could only comment on the help provided by the Red Cross, which Leigh and others were happy to do.

In repatriation group, Leigh is top row, third from left, at Heilig Annaburg. Below, photo of the same facility today by Brennen Jensen of Maryland, whose late father is four in, front row. Brennen contacted me when he saw that I had posted on an online site the same Heilig Annaburg photograph that his dad brought home from his own repatriation.

When he finally got to Vancouver he was greeted by his mother Winnifred Foote McBride, who had not seen him for almost three years. The reunion was particularly poignant because her other son, Capt. Kenneth Gilbert McBride, also with the Seaforth Highlanders, was killed in action near Rimini on Sept. 16, 1944 when his jeep ran over a German mine.

When he finally got to Vancouver he was greeted by his mother Winnifred Foote McBride, who had not seen him for almost three years. The reunion was particularly poignant because her other son, Capt. Kenneth Gilbert McBride, also with the Seaforth Highlanders, was killed in action near Rimini on Sept. 16, 1944 when his jeep ran over a German mine.

Winnie McBride greeting her son Leigh at Vancouver CPR station. She probably asked the Sun newspaper to send her the print when they were finished with it for printing purposes.

From Vancouver, mother and son made their way home to Nelson on the Kettle Valley Railway, arriving in the evening of Feb. 28, 1945 to an enthusiastic welcome party of family, friends, the mayor and other dignitaries. In the coming weeks he was in strong demand as a speaker at service club meetings, and an extensive interview with the Nelson Daily News.

After passing his bar exam he began his career as a lawyer in Nelson. He was never the same physically after the war, as he had nerve damage and hearing loss as well as adapting to life with vision in just one eye. He once showed me where schrapnel was still in his leg because it would be dangerous to remove it. This was painful for him, but he never complained about it, as he remembered so many fellow soldiers who had more serious injuries or died in the war. In the late 1960s his cousin (and former law partner in Nelson) Judge Blake Allan told him he could get an appointment as a judge if he wanted, but Leigh declined the opportunity because, as he told me, it would not be fair to soft-spoken defendants if he could not hear them.

Each year until the 1970s Leigh would travel to the Shaughnessy Veterans Hospital in Vancouver for examination by doctors there. In 1969 he moved to Trail to begin working as a lawyer for the large mining and smelting company, Cominco Ltd. In addition to golf, his hobby in retirement was reading books about Italian art and architecture, an interest he developed while participating in the 30th anniversary of Canadians in the Italian Campaign in 1975. Within a couple of years after retiring from Cominco I 1982 Leigh contracted Parkinson’s Disease, which got progressively worse and resulted in him in 1990 going to a care home in Trail, where he died August 8, 1995 – exactly 42 years after being wounded in Sicily.

The Christmas dinner he mentions in his talk to the Nelson Rotary Club would become famous as the Seaforth Highlanders’ 1943 church dinner in the middle of the Battle of Ortona.

On these maps of German POW camps, Leigh circled the camps where he spent time as a prisoner, and noted the site of his repatriation.

menu on M.S. Gripsholm, page one

menu on Gripsholm, page 2

front page of newsletter for relatives of Canadian POW’s

from POW newsletter

Oflag 7B mentioned in POW relatives newsletter, December 1944

Oflag 7B again mentioned in Canadian POW relatives newsletter

Oflag 7B facilities today, used for police training