by Sam McBride

The following letters were written to relatives in 1915 by Gerald Hamilton Peters (1894-1916), brother of Frederic Thornton “Fritz” Peters.

The letters were kept among the Peters Family Papers by his mother Bertha Gray Peters (1862-1946), then after her death by his sister Helen Peters Dewdney (1887-1976), and most recently by his niece Rose Pamela “Dee Dee” Dewdney McBride (1924-2012). I transcribed the letters in 2008, providing notes where relevant but without corrections to grammar, so as to retain authenticity.

Gerald to his mother Bertha (undated and ripped) early 1915

…It is beginning to get rather exciting. I wonder how long we will be kept in England training. I do hope I can get in touch with Jack. How thankful I am that you are going1. It would be lonely work going so far away, if I didn’t know you would be so close…

1 – Bertha was planning to go to England in early 1915 to be near her sons.

Gerald to Bertha (undated and ripped) early 1915

…You will probably find it easier to get money from Father before leaving than when you are safe in far off England…

…How proud you must be about Fritz. I got your letter and Aunt Florence’s1 on the same day telling me of it. You must almost want to go back to Prince Rupert to be able to tell everyone…

…Beyond an occasional dime I have not had to lend any money.

Your loving,

Zarig2

Beetle Gorgeous toad3

1 – Bertha’s sister Florence Poole, who lived inGuildford,England, southeast ofLondon

2 – a pet name Gerald used in referring to himself and his mother

3 – other pet words used in writing to his mother

Gerald to Bertha (undated and ripped) early 1915

{PREVIOUS PAGES MISSING}

…it would have been fifty times better if you had been there. But we won’t be over till nearly the end of May and we are sure to get at least six months more of training, so you are sure to be over long before we cross toFrance.

We had another field day today, hard work but I didn’t feel it nearly as much as last week. It is wonderful the way one gets used to it. I am so glad we are getting down to real work. This is more what I joined for – a few weeks of it will make me a different being. Tomorrow we set out at 8 o’clock for all day, to be inspected again by the Duke of Connaught1. We are to have blank ammunition I believe. Rather exciting, almost like the real thing.

Maisie is about the same, sometimes quite all right and sometimes very hysterical and uncontrolled.

I haven’t forgotten Mrs. Philpott, and will do my utmost to see her, unless I am on duty that night.

Good bye for a few days my night-blooming-serious. Don’t imagine you won’t be able to make England. We will beat the old hoodoo yet, surely fate won’t be so mean next time.

Your loving,

Beetle

1 – The Duke of Connaught was Prince Arthur, third son of Queen Victoria. As Canada’s Governor-General from 1911 to 1916, he actively supported improvements in military training. He lent his name and support to the raising of the 7th Battalion (British Columbia Regiment), also known as the Duke of Connaught’s Own Regiment. His daughter, Princess Patricia, also helped establish a regiment, the Princess Patricia Canadian Light Infantry, which had experienced troops at the start of the war and would go on to many honours in both world wars and beyond.

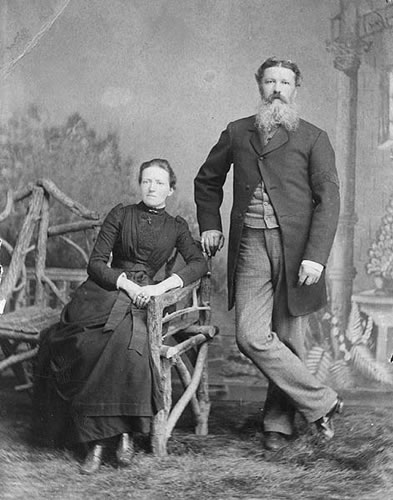

Lieutenant Gerald Hamilton Peters, spring 1916

Gerald to Bertha (undated and ripped) early 1915

How much {money} do you think you will need {to get to England}. I don’t think you should cut it too fine. You must have a safe surplus. Do you intend keeping enough for your return fare? After all, Jack and I should be able to help… Noel is settled, but for that I don’t believe you could ever have got away, as it is, the prospect looks bright.

I wish you would give me Clifford’s number etc, and also Aunt Helen’s address, although I don’t suppose I will ever need it…

Nothing more to say now. Do write soon. You can’t say I don’t write often. Please don’t think of me as only “fairly happy”. I am perfectly happy, I like the life and I get on very well with the other fellows. They seem to like me, and regard me as a sort of millionaire…

Gerald to Bertha April 5, 1915

My Dearest Zarig,

It is Easter Monday and by rights I should still be in bed, it being only 11:30. But in barracks there isn’t any lying in bed…

I sent the books and the photos yesterday. I gave one to Aunt Mim, and of course you will give Helen what she wants. I don’t like them much. I went to the Abbotts1 all yesterday. Maisie is up but still not better…

No more news of leaving yet. I am afraid it will beVictoriaover again. Our Colonel they say is making such a lot of money he doesn’t want us to go yet…

I should be able to learn to swim. I can do about ten yards, but it is so tiring. But at least I have made a start; the rest will come with practice.

I am getting into the work now, and am feeling more at home in the life…{FURTHER PAGES MISSING]

1 – At their home inMontreal

Gerald to Bertha (undated and ripped) April 1915

…I have spent the morning writing some letters and at the YMCA. I wrote to Fritz and to Edgar1 about the rifle. I asked him to send the money to Helen if he has bought it and if not to return it to Father…

I wonder how you spent Easter this year. Last year I think we went out in Clifford’s launch. I think some day we will all manage to get together again somehow or other…

We are very well off here and so long as we don’t go to Valcartier2 I won’t mind…

…Sometimes I would give anything just for half an hour’s talk with you. I don’t think I could ever really enjoy anything away from my Beetle3…

1 – He is likely referring to his sister Helen’s husband Edgar Edwin Lawrence “Ted” Dewdney. The Dewdney name was prominent inBritish Columbiafrom Ted’s uncle Edgar Dewdney, a civil engineer fromDevonwho built the Dewdney Trail across the mountain ranges of southern B.C. and served as a senior cabinet minister under Sir John A. MacDonald. Ted’s mother Caroline Leigh died when he was four, and his father Walter Dewdney died when he was 11, after which he lived with his uncle Edgar and aunt Jane Dewdney at Carey Castle inVictoriawhen Edgar was serving as Lieutenant Governor of B.C. in the 1890’s. Ted met Helen Peters when he was inVictoriaon one of his many assignments with the Bank of Montreal, and they married in June 1912 inEsquimalt.

2 – Large Canadian training facility in Quebec that was built from scratch under orders from Sam Hughes, who didn’t like the existing training facilities at Petawawa, Ontario. The trainees stayed in tents because there had not been enough time to build barracks for them.

3 – A pet name he had for his mother

Gerald to Bertha April 1915

(written fromQuebec)

My Dearest Zarig,

I have just read yours of Apr 9th and I am so glad you have decided to go {to England}. I have just returned from a field day yesterday. We left barracks at 9 am with lunch in haversacks and were out until 5:30 pm and today we repeated this. Very hard work indeed, about seven miles each way and then skirmishing at the double etc. the rest of the time. I was just about finished when we staggered home to barracks. I got some supper here, and read your letter and the two together bucked me right up. These two days are the first field days I have had and I suppose are an example of what it will be in England. But I feel very well, only very tired, and I think I kept up as well as mostly quite a few fainted, or fell out, as the weather was pretty hot and the mud fierce. But soon I will be telling you everything, I hope, so I needn’t describe it all.

We may still be here when you come through, but there are the usual rumours afloat of leaving on Sunday. I don’t really know at all when we will go. We may wait for the Grampion to sail up the river and leave from here direct. The river is about open now owing to the very mild winter. And again most of all, we may go to Valcartier1. It is impossible to say, but the 24th are said to be as good as any of the rest of the 2nd and I don’t see why they should be left behind.

I will certainly look around at Shorncliffe2 for a cottage or rooms – you couldn’t give me a pleasanter task. But don’t expect too much, as I think we will be pretty well confined to barracks for a while, and also later on when we camp we will probably be some way out of town. But there are always weekends etc. and I think we will not fail to make the most of every hour now. I am glad you heard from old man Jack. I have written to him often but have never heard from him. I suppose we can’t expect too much from the mail service. I got your last letter with Noel’s enclosed and the cuttings and other papers. Certainly Noel doesn’t lack nerve. I am sorry for the people we knew in Victoria. But it is better than if he didn’t like it in which case he wouldn’t stay. He could get his discharge easily enough, and his fellows would tell him so. So it is very lucky he likes it. I don’t think you need worry about Father, I think he is pretty secure. At any rate, I am sure you will never be sorry you made the supreme effort and went. I always knew you would go somehow or other. I hope in a way we go first, unless we go to Valcartier, in which case I hope you come through Montreal first. Valcartier will not be ready until May 15th about. I think there will be awful trouble if the men are sent there, but on the other hand, everyone is so anxious to leave here, that they don’t care much where they go, so long as they escape the friends who daily ask “When are you leaving?”

Will stop, as I am dogging beat, so still I have to lift each leg with great care and slowness.

– Zarig Beetle

P.S. Don’t be angry because I don’t put more Beetles in, every time I write it I think it a thousand times and soon I hope will be saying it. Be sure and let me know in good time when you will arrive here if you finally decide on it, as I have to give some notice to get leave to meet you.

P.P.S. I haven’t forgotten the $15 but am afraid I can’t send it till a little later in the month.

1 – The Valcartier base inQuebecwas the central training and marshalling facility for the Canadian Expeditionary Force. It was built from scratch by the federal government as ordered by Defense Minister Hughes, contrary to Canada’s existing mobilization plan. Conditions for the troops were bad, but that was accepted as part of the training.

2 –A number of Canadian barracks and other military facilities were centred at Shorncliffe, in Kent southeast of London.

Gerald to Bertha April 17, 1915

Khaki Club1

My Dearest Beetle

I got your wire yesterday morning, and I can’t tell you how badly I feel about it. To think you should have been so nearly off, and then to be stopped at the last moment. You must be heartbroken, my poor bedbug. Hard, cruel, damnable luck. I am glad poor Noel is better2 but I suppose it will be a long time before he is about again. Will he be able to return to his regiment, or don’t you think he is fit for it? It seems so hard after struggling against all the other difficulties, to be bowled over by the unforeseen.

Now, my own Zarig, I know you are so brave you will hold up as well as you can, even under this crushing blow. But remember, even now, you may be able to make it a little later on. Surely before August Noel will be all right, and although I suppose the expenses of his illness and your expenses will be pretty heavy, still you may have enough. August seems a long, long time off but it will come at last and surely you can make it then. I will do my utmost to send you what I can, but I am afraid it won’t be too much. I am simply determined that you go toEngland by hook or crook.

I got you first letter in which you said you were almost certain to go on Thursday evening, and was so glad then on Friday morning. I got your wire which simply made me curse everything. We had a hard day all that day, but I couldn’t think of anything, but my poor beetle so terribly disappointed. This morning I got your letter telling me what train you would be on, about getting a day’s leave etc. and that was the hardest of all. If it is bad for me, it must be a thousand times harder for you.

Strange that poor Noel should be the first to suffer out of our family in this cause. I do hope he soon gets better. Thank Heavens none of us drink or smoke. Here is where that will count.

I will try and see Mrs. Philpott, but really I don’t think I will succeed, they won’t allow you on the platform and the Windsor Street Station is so huge that it is almost impossible to find anyone in it. But I will write two notes to her, one addressed care of the Misanabie and the other for the train. If I can’t get her I will post one for the steamer and get a messenger boy to give the other to a porter.

We have been working very hard lately. Last week we had three field days in succession ending Friday. About seven miles march, and then skirmishing all day and the march home. I was so stiff by Friday that it was simply agony to drag each leg along, but I am glad I was able to hold out. It is very healthy work, all in the open, and I feel very fit after it. I am glad we are settling down to hard work at last.

I do hope, my Zarig, that you won’t give up hope altogether. Remember how many difficulties have been smoothed away settled, and Helen3 is far better off than when you first thought of going toEngland. It will mean a long delay, I know, but sooner or later you will make it. Of course I know how sickening it is, when it would have been so nice crossing with Mrs. Philpott, and going right away.

Please be sure and let me know what your plans are, how long must you stay in hospital, and if Noel can go back to camp again when he is better.

How I wish I could be with you to try and comfort you a little after this awful blow. I always think disappointment is the hardest of all things to bear, and you have anxiety about poor Noel into the bargain. To think that in a week you would have been with me again. How I wish it could have been me that was the loser instead of it’s always being you that has the rough time of it.

Your loving Zarig

Beetle Beetle Bedbug glorious toad

1 – Khaki, from Persian for “dust-covered”, was a common fabric and camouflage colour for military uniforms. To be “in Khaki” in World War One was to be in military service. Later in the war years, gangs of women would accost young men in civilian clothes, say “why aren’t you in Khaki?” and plant a white feather symbolizing cowardice on the man’s coat or shirt. Khaki Leagues were formed across Canada to support soldiers and veterans. Gerald was apparently writing this letter in the recreation room that the Khaki League in Montreal provided for soldiers starting in December 1914.

2 – The problem with Noel isn’t specified. It sounds as if he had something like a nervous breakdown. It caused Bertha to cancel the arrangements for her trip toEnglandat the last minute, which was extremely disappointing for her and for Gerald.

3 – his sister Helen

Gerald to Bertha (ripped and fit together) April 20, 1915

Khaki Club

My Dearest Zarig,

I am longing to hear from you again, and to find out how things stand exactly. It will be too awful if you have given up all hope of ever going to England. You must still make it your aim to get there sooner or later. Sometimes I think I wouldn’t have left Prince Rupert at all had I known what was to be, not that I am sorry for myself, but really I think you are having too big a share of hard luck. I miss you dreadfully now that the prospect of seeing you soon has gone, it makes it so much worse. The awful distance makes me feel I was buried under the ground, it gives me just that feeling of suffocation.

Do make every possible effort to cross later on, when Noel is a bit better and you have had time to recover financially.

We have no further news of leaving yet. I think it must be Valcartier next month. I don’t much mind now, as you wouldn’t be in England. Still, I hope we are sent across.

I was on quarter guard again yesterday and feel rather tired, so I won’t continue now. Try and not be low, my cream of wheat, surely it will only be a matter of a few months before you can make it. Goodbye, my crawling snake.

Your loving

Beetle

P.S. I wrote to Jack and told him about Noel, and also gave him your address

Gerald to Bertha April 27, 1915

Khaki Club

My dearest Zarig,

I was delighted to get your letter of Apr 19th. I think it is splendid of you to be able to get away as soon as you intend. I greatly feared you couldn’t make it until the fall. You are very wise to take the chance, especially since this last dreadful battle. I suppose you are on tenterhooks about Jack, but you would be wired from Ottawa right away if anything happened. But you see what it would be like to be in such awful suspense all summer.

I strongly approve of you going. I will send you $20 on May 1st. I do hope Jack is able to send the $50. I haven’t much time to write this, as I must hurry down to meet the St. John train. Your wire, which I enclose, said Apr 27th but I am sure it should have been the 22nd. Unfortunately, I didn’t think there would be a mistake until too late, and will meet the train on the chance the Missanabe sailed Apr 23rd. I doubt if we will be here by May 20th, but we may be delayed in which case you may be sure I will get two days leave and spend it all with you. I hope I will still be here and there is a good chance of it. How glorious it would be, only three weeks, I can’t realize it. I think it is a splendid plan sending Noel to Helen. He will like it and it is better for father. Be sure to tell father how he wanted to go and also say that he wouldn’t hear of staying with her unless father paid $25 board. Otherwise he will be slack in paying it.

Will write again tomorrow as I must fly to train although I know it is useless.

Your loving Beetle

Gerald to Bertha May 4, 1915

My Dearest Zarig,

I am afraid I can’t send you the $20 as I promised in this letter, but I will leave it in a letter here for you to get on your way. There are a lot of small expenses incidental to our going away that I hadn’t counted on. But I hope you won’t need it until you arrive here. I don’t think there is any doubt that we are leaving this Saturday or Sunday, May 8th.1 The Thespis and the Metagama are in port now, and I hear we are also to have the Misanabie in which case your passage will probably be cancelled. I suppose that wouldn’t much matter as of course you would be given another booking. It is rather hard luck your coming just after we pull out, but I think no other earthly power would have moved the 24th but our old friend the hoodoo. I would sooner leave now though than be kept here all summer. I will send you our new address as soon as we are told it, if possible in my wire. You know the correct order to put it in so I can just put the brigade number as our regimental number will be the same.

This will be the last letter I will send to Rupert as this should arrive on May 11th. I do hope Helen was able to send you the $20 etc but I fear she will have paid Waitts with it.

We will not see each other for over a month, I fear, but still it won’t be so bad as there will be so much for both of us to do. I will send a wire to you c/o Aunt Florence2. I expect they won’t give any leave for a few weeks.

{FURTHER PAGES MISSING}

1 – Gerald’s army file shows that he arrived inEnglandon the Cunard ship S.S. Cameronia on May 20, 1915, which was 12 days after the R.M.S. Lusitania was torpedoed and sank off the coast of Ireland. Interestingly, Cunard authorities and the British government insisted until January 1917 that the Cameronia obeyed rules of neutrality and was not used for troop transports. On April 15, 1917 a German submarine torpedoed and sank the Cameronia en route from Marseilles to Egypt, with a loss of 210 lives.

2 – Bertha’s sister Florence Poole in Guildford, Surrey, England.

Gerald to his mother Bertha May 9, 1915

My Dearest Beetle,

I received your night wire on Friday and also your letter of Apr 28th. I sent you a wire last night. We are embarking tomorrow at 9 pm and probably sail at midnight. I don’t know what boat we are to be on but think it is the Corsican or Corinthian. I am not sorry to be off at last, although I wish you could have come here first. Still you would have missed me even if you had sailed on the 20th. I wasn’t surprised to hear that the Massanabi was taken, but I don’t know where she is at present, or who is to cross on her. I do hope you won’t be delayed this time, surely the third time should succeed. It is rumoured that we are only to be kept in England about one month and then sent over to France. There is a good range at Shorncliffe1; a few weeks on it should make our men good enough shots. I hope this is true, as the training is pretty monotonous and we may as well get there as soon as possible. As far as getting killed is concerned, you are as likely to be shot in one day as in several months of it.

We heard on Thursday that we were going this week but no one believed it. On Friday all our rifles were packed and everyone realized that we really were off. Forty-eight hours leave was given us from Friday evening to Sunday night. I slept at Aunt Mim’s2 between sheets for the first time in three months and it certainly felt luxurious. This morning I slept until 11 am and then Aunt Mim brought me my breakfast in bed. I took Maisie to the Orpheum last night to see “Seven Keys to Baldpate”3, very American but not bad. Maisie is nearly all right again now.

It felt strange last night to be in a real bed again. I tried hard to imagine I was back in my little room at home, then I remembered how I scratched on the wall and you answered. If ever this war is over we won’t be parted again, my Beetle. I don’t know whether to be glad or sorry we are off. I feel so excited about it – so many things may happen. I am going to try at once when we are over to exchange into Jack’s company. There are a few nice fellows in our platoon. I like one fellow named Bertram from Jersey, he seems to be a gentleman and quiet. I quite like another fellow, Payne, but he is about the same class as Sarre. He saw Fritz some years ago at Chatham. Of course, I suppose he never knew him as he is only a mechanic of some sort, but very decent.

I am enclosing $10 in this. I can’t say how sorry I am to have to break my promise and only send $10 instead of $20, but there had been so many small items that I had forgotten. I will try to send you some more when we are paid again, but I am very much afraid that when we reach England we are only given thirty cents a day, and have the rest held back until the end of the war. I suppose it would be a huge problem if they let loose all the soldiers after peace was declared if they were all penniless. But we have not been told anything for sure yet. I hope this tenner gets to you all right. I know it is risky sending it like this, but can’t get a MO today and don’t want to ask Abbotts to get one. Aunt Mim might think it odd.

That wretched barrel wouldn’t work as the lid wouldn’t fit. We got a box instead but couldn’t get it quite big enough, so I am leaving the blanket here. I notice Aunt Mim seems very short of them and I suppose Helen will have plenty now if the house is partly furnished. By the time we got the box all packed it was too late to send it off, and Aunt Mim wouldn’t let me go to the station with it as the freight sheds are right at the other end of town, and it would have taken all the afternoon, my last one, to get it off. She has promised to get it off herself. I will leave enough to cover the freight, and she can give you anything over if there is any. I know I would never have the power to get it off…(PAGE MISSING)

…The only redeeming feature is that so many Americans were drowned4. Of course the States won’t do anything. You ought to get a big reduction since this. A fellow I know whose wife has just crossed by a Canadian line got about $15 knocked off, as he threatened to travel USA otherwise. The Stars and Stripes are a certain amount of protection. I don’t think you mind the risk of being torpedoed, although there certainly is a very big risk now.

I may as well end now. How much I long to see you can’t be told in writing. When you arrive here, go to the old high school on Metcalfe and you will see where I have been the last three months. It is hard to realize that it has been a quarter of a year. I have had a pretty good time, far better than I had expected.

I am glad you had a fairly decent day for your last in Victoria. You are right about the Empress5, it is the only hotel that I have ever liked at all. I well remember Love in Idleness.

I suppose Jack must have come through safely or you would have heard by now. I will try to write you from Quebec, but I don’t think they will allow it, so this is probably my last from Canada. If we cross quickly I will write you care of Aunt Mim. I don’t think it will get here in time. Goodbye my crawling toad. Zarig. Beetle.

1 – in Kent, southeast of London

2 – Mim/Mary Abbott, who lived onGrosvenor Road,Westmount in Montrealwas Bertha’s sister. Maisie Abbott was her daughter and Gerald’s cousin

3 – A play written and produced by renowned American writer/composer/performer George M. Cohan, best known for writing patriotic songs like “Over There” and “Grand Old Flag.”

4 – He resumed writing the letter after hearing of the sinking of the Cunard liner Lusitania by a German torpedo.

5 – The Canadian Pacific Railway’s Empress Hotel in Victoria B.C.

—————————————————————————–

Gerald to his mother Bertha May 18, 1915

HMS Cameronia

My Dearest Zarig,

I am writing this on the chance of its reaching you before you sail. We are now within the danger zone and our machine guns are mounted. Tomorrow no man will be allowed on deck, and we will wear our life preservers all day. We have had boat drill every day and everyone knows where it go. But if you are torpedoed of course they would smash up all boats launched full of soldiers. We have no escort, but may be met tomorrow. No one has any idea where we are to land but all seem sure we are bound for Shorncliff. I won’t be sorry when we land although the trip has been good enough fun. The first four days we were in clover, but then we were moved to the hold, where all B Companies had been, and they were given our staterooms. It certainly is pretty rough. We are herded together in bunks about 2 feet by 6 and 3 feet high open all around, and at the bottom almost of the ship, and we eat on tables built in an open space in the middle. There is what Clifford would call a “miasma”. Some say cattle were kept there, but the general opinion is that it is hardly good enough for them. But everyone treats it as a joke, and it is only for a few days. My heart sank I confess when we were marched down below the decks and into this weird place, but it hasn’t been so bad really. I sleep well enough, although I have my doubts as to what company is in the mattress. So far I have seen nothing but some men have strongly expressed the feeling that it is “bugs”.

I needn’t give you any account of the trip as we will so soon meet. I will post this as we arrive, probably Thursday, May 20th. In less than a month we should be careering around London together.

May 21 – Arrived here 1 am this morning, address Private G.H. Peters 65781, 12th platoon, C Coy, 24th Battn Victoria Rifles, 2nd Can Exped Force, Sandling Huitments, Kent.

We are near Shorncliff and in huts very clean and comfortable.

Your loving Zarig. Beetle, glorious bug.

———————————————————————————

Gerald to his sister Helen July 17, 1915

Sandling Hutments1

My Dearest Ode Hagen,

I should have written before, but I waited to hear more news of Jack2. I suppose you know he was reported missing since April 25th. Aunt Florence told me this in her first letter. Yesterday she wrote saying that Aunt Helen has found out through some friends of hers in Switzerland that Jack is a prisoner in Hanover3. It is a great relief to hear he is still alive. I was afraid he had been killed in the fighting around Ypres Apr 24-27. About 350 officers and men of the 7th were captured with him. It is hard luck, but it might have been so much worse. I am sorry to hear that Mother heard he was missing before he was located. I am afraid she must be terribly upset and anxious. She is due in England any time now, evidently she traveled via Havre on the Sicilian which takes 12 to 14 days. I expect a wire from her either today or tomorrow. She is coming straight down to Hythe4, as there is no prospect of my getting any leave for some time yet. We are allowed six days, but only a few at a time, and none until our course of musketry on the range here is over. I have written to her care of the Union Bank5 telling her Jack has been traced. I suppose he has written to her inPrince Rupert and so I cabled Father to open all letters from Germany and cable his address to Aunt Florence. At least we will be able to send him weekly parcels of food etc and also some money, as most of the camps for prisoners have canteens where they can buy stuff if they have any cash. Poor old Jack, what a blow to all his hopes, but he is the sort to make the best of it and he is pretty sure to pull through all right. At any rate he is far safer than he would be in the trenches.

I got a cheery letter from Fritz yesterday. He hadn’t heard Jack was a prisoner for certain and said that after all, one of us three at least was bound to be killed. He doesn’t expect to get any leave before August so I won’t be able to see him until then. I am longing for Mother to come, she intends taking a little cottage or flat in Hythe for a while. I could spend a few hours every evening with her and you could imagine how jolly it would be for me. I am more than contented with our camp life at present. The work is harder than inMontrealbut more interesting and the weather has been glorious so far, not like English weather is as a rule. We get up at 5:30, drill from 6:30 to 7:30 generally physical training, running etc.; breakfast at 7:45, drill 8:45 to 12:45, bayonet exercises, musketry, trench digging, or route marches; dinner 12:45, afternoon parade 1:45 to 5 pm, then tea. You can leave camp from 5:30 to 9:30 pm every night unless there is a night parade from 9 to 11 pm. We have these two or three times a week. We do nearly all our drill and marching with full kit, so you see we are kept pretty well at it.

In comparison to the First Contingent we are simply in clover. We live in long wooden huts 30 men in each, with a bed made of three boards raised a little off the floor, a mattress filled with straw and three double blankets. The huts are very clean and bright and airy. We eat at tables down the centre of the room, good food and lots of it. So far I haven’t had a single hardship, and scarcely even a discomfort. Next week we go down to the ranges every day for target practice. I rather dread this, as I know I will make a fool of myself. These new “Mark 7” bullets the Ross fires6 kick like the dickens, and I doubt I will hit a target. However, there are lots of others who can’t shoot as well. They haven’t time to teach everyone now to shoot well, and it isn’t really essential to be a crack shot. We were reviewed by General Steele7 the other day, and O.C. of the second division and he praised the 24th quite a lot. I don’t think we will be kept inEngland long. There is a rumour that Kitchener and the King are to review us in a fortnight or so.

I had a rather exciting time last Saturday afternoon in Folkstone. Last week was “duty week” for the 24th Battalion, which means that all the pickets and guards etc. for the neighboring towns are taken from the 24th. Each battalion takes a week in turn. I was one of the 30 men for picket in Folkstone on Saturday from12 to6 pm. There were four pickets, 8 men and an NCO to each. We did nothing all the afternoon, no drunks to arrest, and at6 pm we lined up to await our relief. We waited two hours and then got a phone from camp couldn’t get down to Folkestone, on account of the motor lorry breaking down, and ordering us to “carry on” until 10 pm. We had had nothing to eat sincenoon, and were feeling pretty desperate, especially as half the picket were nearly drunk from numerous beers taken while on duty. So our sergeant marched us off to get some supper at his own expense. On his way to a restaurant we met a military police who told us to double up as there was a big fight on. We flatly refused at first but on getting nearer we saw it was getting serious and so we had to hurry into it, to try and rescue a policeman who was being mobbed by enthusiastic Canadians. Then began a riot that lasted untilmidnight. Several were injured and one killed. A squadron of cavalry turned up when it was all over, too late of course. We had a hell of a time, I don’t know what we were meant to do, but everyone was bent on “smashing” the picket. We were pretty well all in when we got home at1 am, and had to go to bed without anything to eat, and in the dark.

…I have just received your letter of May 20th. By now you will know old man Jack is still alive, as Mother will cable you. The suspense must be pretty hard for you, so far away it seems worse I know. I also have just got a wire from Zarig. She has just arrived in London. I am dying to see her. I wired to her to come down here at once. I couldn’t wait for her to go to Guildford first. She asked after Jack and by now she must have got my answer telling her he is a prisoner. I am thankful she is out of the suspense at last. I expect her tomorrow night, and will meet her train at Hythe by hook or crook, though of course I am on duty tomorrow… however I must manage it somehow. I want her to stay at the hotel here for a day or so while she gets a cottage or flat. I couldn’t get one as I am not good at that sort of thing, and I don’t get much time for looking around. England is such a weird place too, that one never quite knows what sort of house it is all right to live in. As a rule, if you see a very nice little cottage it turns out to be an almshouse. It is awfully good for her to want to stay in Hythe as it will be pretty dull for her all day long.

I don’t see how I can wait until she arrives. I thought she would have been here by June 10th on the Metagama8 but evidently that sailing was cancelled as she came by the Sicilian via Havre and thus was a week longer. This last week has seemed a year long. I grudge every day, as I don’t think we will be in England very long. It is rather exciting to be getting nearer and nearer every day. The stories told by wounded men aren’t extra inviting, but it must be all fate I suppose. There is very little “fair play” in this war – all the new bayonet exercises are made to take in every possible trick that before would be considered very unsporting. Also, the standing orders seem to be to kill all the wounded. I expectEngland will soon use gas. I am afraid it will be necessary, but it is a hellish thing. It is awful to see the poisoned men, black in the face and unable to breathe.

But now of course the men are provided with respirators etc. I only hope if I am wounded it will be in some civilized part and not in the stomach etc. where you can’t ever tell people about it.

I had such a dreadful disappointment a few days after our arrival. I got a letter in Jack’s writing, and I thought he was safe, as he said he was unhurt and well. But then I saw the date was March 11th. He had addressed it to the Army P.O. London as he thought I would be over by then, and they had held it until the 24th arrived.

I have just received another wire from Zarig. She arrives here on Saturday afternoon. How I am longing for it to come. If only you were there too, what a time we would have. How I sometimes look forward to the end of this doggasted war, when we will be together again, if we are lucky enough to all pull through. I think it may end in six months, certainly not before, probably long after that. At last,Englandis beginning to see what she is up against. The damn fools who insisted on being “optimistic and cheery” are realizing it is largely their fault that we are making such slow progress. That miserable attack onKitchenerby the Daily Mail was ungrateful and mean, but it is true we are short on shells. I don’t see how they can say there are many slackers here. I never see anyone in plain clothes around.

Don’t be too low about old Jack, he will be all right. He is the sort to get through an affair like this, and he is with many of his comrades. It will not be nearly so bad for him when we get in touch with him, which no doubt we soon can do. Also, Hanover is the best place for prisoners, as it is the Prussians and Bavarians that are most bitter against us…

[further pages missing]

1 – Canadian barracks in Kent

2 – Jack was listed as “missing” in the 2nd Battle of Ypres. His battalion was among the hardest hit in the battle. We don’t know how Jack died, but his body was never recovered, and most deaths in the battle were from the huge number of artillery shells launched by both sides on April 24, 1915.

3 – A combination of poor communication, wishful thinking and rumours led the family to believe that Jack was alive as a prisoner of war. His service file shows that on July 3, 1915 J.F. Peters who was previously reported missing, was now “unofficially reported a Prisoner of War at Celle Lager, Hanover”. However, onAugust 8, 1915Jack was noted as “still missing” and then onMay 29, 1916the note in his file states “The soldier interred at Celle LagerHanoveris proved to be not identical with above, who is still missing. Now, for official purposes, presumed to have died on or since 24-4-15”. After getting their hopes up, the news must have been devastating to the family, who within a matter of weeks would learn that Gerald was also dead. The family – especially Bertha — still held out hope for Jack, but that faded over time, especially after the armistice.

4 – Hythe is a small market town on the coast in Kent four miles from Folkestone, where today the Channel Tunnel goes into the sea.

5 – Gerald formerly worked at the Union Bank in Prince Rupert, and was apparently using his contacts with the bank to have mail set aside for his mother who was travelling to England.

6 – After the Ross Rifle jammed terribly at Ypres, Canadian authorities opted to try to fix it rather than replace it. Here they have designed a different type of ammunition for the rifle, but soldiers found that it still jammed. Despite ample evidence that the rifle just would not work in battle conditions, Hughes and his allies insisted that the Ross continue to be used rather than the British alternative.

7 – Major-General Sam Steele was one of the great characters of the history of Western Canada, perhaps best-known for leading the North West Mounted Police in keeping law and order during the Klondike Gold Rush of 1898. But he also came from a military background and served in virtually every battle from the Fenians Attack of 1866 until the First World War. He applied for active service in 1914 but was initially denied on account of his age (65). However, he received strong support from Minister Hughes, who wanted Steele to command all of the Canadian troops in Europe, which created complications because two British generals already had that responsibility. This was one of many bitter conflicts between Hughes and the British. Steele was knighted in January 1918, retired six months later, and died in 1919.

8 – The Metagama was a Canadian Pacific Railways passenger ship. As it was just two months since the sinking of the Lusitania, relatives must have been relieved to hear that Bertha landed safely inEngland.

Gerald to sister Helen November 28, 1915

Belgium

My Dearest Ode Hagen,

I should have written before, but I hate writing unless I use a green envelope and we only get one a week and I use that for Mother. This should reach you about Christmas. I am enclosing a handkerchief made by the Belgian peasants. They make lace with scores of pins. I hope you like it, but I don’t know anything about lace. However, it has the merit of being made within the sound of the guns.

It is pretty quiet on our front just now. We never do any fighting at all. In fact, I have only had one occasion on which I have really been under anything like a hot fire. That was one night during our first spell in the trenches when I was in a working party, digging a new trench in front of our lines, only about fifty yards from the enemy. It was a dark rainy night when we started digging, and for half an hour or so we were not seen, as we crouched down when the flares were up. But then the clouds cleared away and the moon came out. Then they saw us and started firing. We kept on for a while digging but then a few men were hit and we were ordered to lie down and try and keep under cover. The trench wasn’t deep enough to protect us properly, and a few more were hit. One man a few yards from me was shot in the stomach. You know what that means and it was very sickening hearing him. I certainly felt pretty queer, and not at all heroic. Their beastly explosive bullets kept hitting all around me knocking the mud into my face. Imagine me crouching there, knowing only too well that I wasn’t properly covered. However we got back safely, and the trench was finished by degrees.

We also had what Headquarters call an “exhibition”. Our artillery bombarded the German trenches hard for an hour and a half, and then we threw smoke bombs to hide our trenches and kept up rapid fire for some time. I got away about 120 rounds, and then my rifle was too hot to hold. The Germans sent bullets whistling around but they soon lost sight of us through the smoke. The whole affair was only to cover one of our attacks farther down the line. It was pretty exciting when the German artillery started replying. Of course all our men were in the slits, which are practically shell proof, but I happened to be sentry at the time, so had to remain in the trench alone. The shells make a tremendous screaming, but they didn’t do much harm to our trenches.

There is some talk of our getting a week’s leave soon. I am longing for it – how lovely to get back toEnglandand to see Mother again.

Cousin Agnes has been {FURTHER PAGES MISSING}

—————————————————————————————–

Gerald to his father Frederick November 30, 1915

Dear Father,

I have now been in and out of the trenches several times. Things are very slack, and I have seen very little excitement. However, we shall no doubt get plenty of it later on. The life seems to be doing me good, at least everyone tells me I am getting fat on it. Of course, everything is made easy for the second contingent, we have no hardships to endure as did the first. So far I have witnessed one fairly good artillery bombardment, which we began and the Germans answered, and occasionally we have been under fire while on working parties etc. But as a rule there is little danger or excitement.

I went down to the place where Jack’s company is billeted about a week ago. It is some distance from here. Unfortunately most of the men were away. I saw one fellow who had known Jack at Salisbury. But he wasn’t near him at Langemarke. However, he promised to make enquiries and I left my address with him. At least so far we have not heard of anyone who actually saw him killed. I think there is a strong possibility of his being wounded and a prisoner in Belgium.

Well, it isn’t much use my wishing you the usual Christmas wishes this year. We can only hope that next year we will be a less scattered family again. I would like to see old Prince Rupert again. The muskeg would be a welcome change from the appalling mud here. Please give my respects to Mr. Broderick and my best wishes to the other fellows there.

You certainly were a prophet when you said that the war was far from finished.

Your affec son

Gerald

Gerald to sister Helen December 7-8, 1915

{PREVIOUS PAGE MISSING}

…I couldn’t post this before, as I have been unable to get the handkerchief, but I will send it on later. We have been away from the village we are generally billeted in for a long time, and I expect to go back there in about a fortnight. Christmas we will spend in the trenches1. I received your letter and the newspaper clippings. It is so jolly hearing from you. I wish I could write oftener, but it is such a terrible business under these circumstances. We are now in a barn, half full to the roof with straw, so it is like being on a haystack. The place shakes like jelly. It is warm and comfortable enough but not made to write letters in. I don’t think you should give up hope of Jack. I think it is quite possible that he is in Belgium. But I fear he must be very badly wounded and he must be having an awful time. I am glad you are learning rags2. I know what you feel about good music. This war will about dish my hands of learning – a year more of this work and my hands will be horny and hard…{PAGE RIPPED AND TEXT MISSING}

…Wait until you have waded for a mile through thick, sticky mud, knee deep literally. Your fat seems torn off you, and you are all in.

I would love to see the Baby3 again. The sixth was its second birthday, wasn’t it? She (beg pardon for the “it”) must be very cute now.

…I do so look forward to seeing you again. It is a year and a half now since I left Vernon4. Isn’t it bughouse the way all of us are scattered about. We were such a happy family once. Let us hope the future will be kind.

Well, goodbye now, my dearest Ode Hagen, and a decent Christmas and better New Year.

Your loving Zarig

P.S.: I will send the hanky as soon as possible.

1 – Gerald’s service file shows that he embarked forFrancefrom Folkestone onSeptember 15, 1915. In a subsequent letter in January 1916 he talks of being at the front for four months, so he must have gone to the front inBelgiumsoon after arriving inFrance.

2 – “rags” as in piano music of the time

3 – He would have met baby Eve Dewdney, who was born December 6, 1913, when he visited the Dewdneys in Vernon before they moved to Greenwood. Eve married Jack Fingland in 1933 and died in December 2002.

4 – Ted and his family were in Vernon where he was an accountant with the Bank of Montreal before moving to Greenwood as a branch manager for the first time in 1915 and then to New Denver in 1916.