“I wish you could have known Dally,“ my mother, Dee Dee, said to me hundreds of times over the years.

Bertha with pet dog in Victoria, British Columbia, circa 1905. Family ciollecgtion.

Also: “Dally was so smart!“, “Dally was interested in everything“, and “Dally would have known the answer to that question“.

Bertha`s father, Col. John Hamilton Gray, who was host and chairman of the historic Charlottetown Conference of 1864, is featured in this sculpture in downtown Charlottetown, Prince Edward Island. Sam McBride photo.

Dally was the nickname used by Dee Dee and her siblings for their maternal grandmother, Roberta Hamilton Susan Gray Peters, who lived with her daughter Helen Dewdney`s family in southeastern British Columbia from 1916 until her death three decades later at age 84. Her sisters in the Gray family called her Bertie, and she was known in the community as Bertha, which is how I choose to refer to her. No one in the family recalled the origin of the nickname Dally.

As a boy, I found my mother`s lavish praise of her grandmother somewhat annoying. My thinking was: she died five years before I was born – why talk so much about someone I am never going to meet?

In recent years, however, my research into the life of her son, Victoria Cross recipient Frederic Thornton “Fritz“ Peters, has given me insight into why Bertha was so memorable to Dee Dee, as well as other family members and friends. I was impressed that one person`s life could span so much of Canada`s history, and that her spirit and sense of humour held up despite experiencing a stream of disappointment and tragedy during her years as a mother and widow.

The Gray family residence known as Inkerman House, where two-year-old Bertha was introduced to the Fathers of Confederation who were invited to Inkerman by Col. Gray to an after-dinner party on Saturday, Sept. 3, 1864. Family collection

At age two in September 1864, Bertha was brought forward and introduced to the Fathers of Confederation her father brought home to the Gray estate known as Inkerman House from the Charlottetown Conference for an after-dinner party. Eighty years later, in February 1944, she received, as her late son Fritz`s next-of-kin, the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross medal from a delegation of American officers and brass band representing President Roosevelt and General Eisenhower.

Bertha was the youngest of five daughters of Col. John Hamilton Gray and Susan Ellen Bartley Pennefather. Sister Mary Stukeley Hamilton Gray was three years older, and the other three sisters were much older. The eldest sister, Harriet Worrell Gray, 19 years her senior, was out of the house before Bertha was born, as the parents sent her as a teen-ager to England to live with, and care for, her aging Pennefather grandparents. Sisters Margaret Pennefather Stukeley Gray and Florence Hope Gibson Gray were, respectively, 16 and 14 years older than Bertha.

Painting of Bertha`s mother Susan Bartley Pennefather at age 17, shortly before her marriage to Col. Gray. Family collection.

After Susan`s death in 1866, Margaret assumed the “mother“ role for her younger sisters. Florence took over in 1869 after Margaret left home to marry shipbuilder Artemus Lord. A couple of weeks after Margaret`s wedding, the widower Col. Gray married Sarah Caroline Cambridge, and they would have three children, of whom only Arthur Cavendish Hamilton Gray survived to adulthood.

In addition to tutoring their little sisters, Margaret and Florence did their best to shield them from angry outbursts of their stern father, whose career as a British Dragoon Guards cavalry officer left him obsessed with discipline and punctuality.

In a family of ardent readers, Bertha stood out as the most voracious reader of them all. In addition to the large family collection of novels, poetry and history, Bertha`s thirst for knowledge led her to read through dictionaries and encyclopedias. In later years, her wide-ranging knowledge helped Bertha win cash prizes as a solver of difficult crossword puzzles in contests sponsored by newspapers.

Bounding with energy, young Bertha was always up for outings, and encouraged her sisters to organize social events that included her. Regarding her father with a mix of fear and admiration, she enjoyed participating in discussion of current events and politics at the dinner table. As descendants of United Empire Loyalists, the Grays were wary of the United States of America, which was slowly recovering from its Civil War in Bertha’s girlhood. The Grays saw no conflict in being strongly pro-British Empire and at the same time proud Canadians. Throughout her life, Bertha introduced herself to new acquaintances as a “Daughter of Confederation”, since her father was a Father of Confederation.

Painting of Margaret Carr Bartley c. 1830, around the time of her marriage to Major Sir John Lysaght Pennefather. Family collection.

A common topic of sister talk among the Grays was the mystery of their grandfather Bartley`s family. Their mother Susan was born in Jamaica in about 1825, the only child of Margaret Carr and Lieut. William Bartley of the 22nd regiment of the British Army. As was common for soldiers stationed abroad in that era, Bartley became ill and died in Jamaica. His commanding officer, Major Sir John Lysaght Pennefather of Anglo-Irish aristocracy, took charge of looking after the widow and baby. He later married Margaret, who gained the title of Lady Pennefather. Her new husband insisted on being recognized as Susan`s father. Communication with the Bartley relations ceased, and Susan did not learn of her real father until told just before her marriage to John Hamilton Gray.

Bertha and her sisters speculated about titles and inheritances they could have missed out on because of the loss of contact with the Bartleys. This led Florence to take on the role of family historian. Bertha`s handwritten copies of Florence`s inquiry letters and replies exist today in the Peters Family Papers.

Florence left home in 1876 to marry mining executive Henry Skeffington Poole, settling first in Stellarton, Nova Scotia and after 1900 in Guildford, England.

By 1880 both Pennefather grandparents had died. Released from caregiver duties, Harriet married Rev. Henry Pelham Stokes in London later that year.

Bertha’s eldest sister, Harriet Worrell Gray (1843-1882), was 19 years older than Bertha. Harriet looked after her Pennefather grandparents in England, and married Henry Pelham Stokes in her late 30s after the grandparents had both died. Family photo.

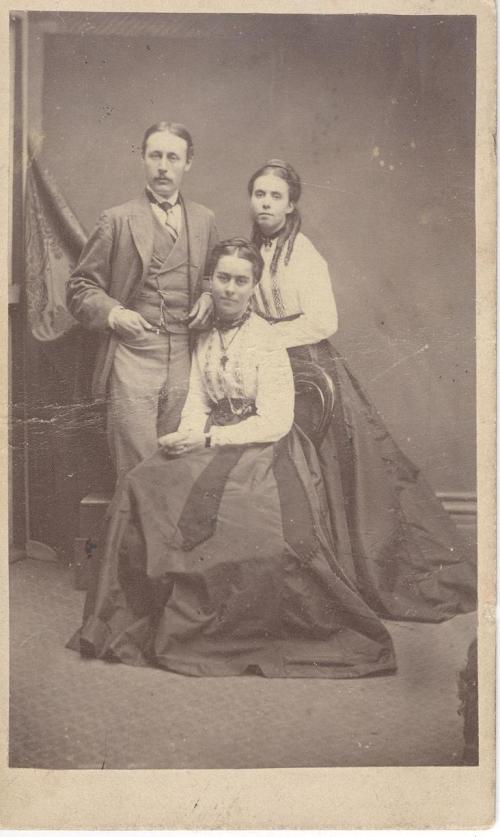

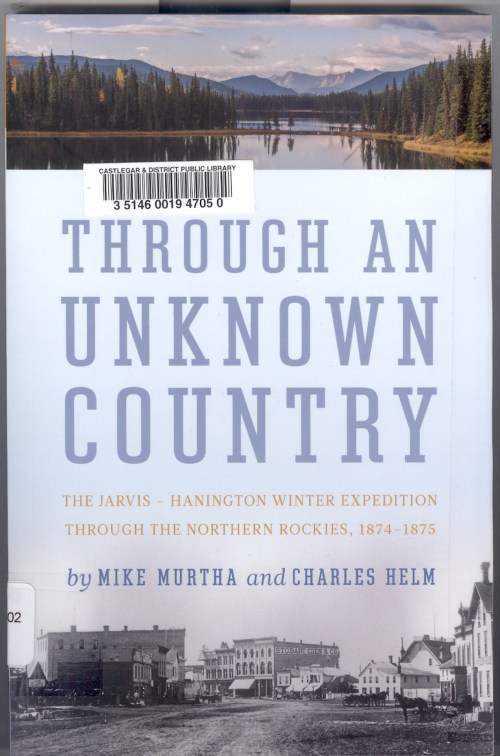

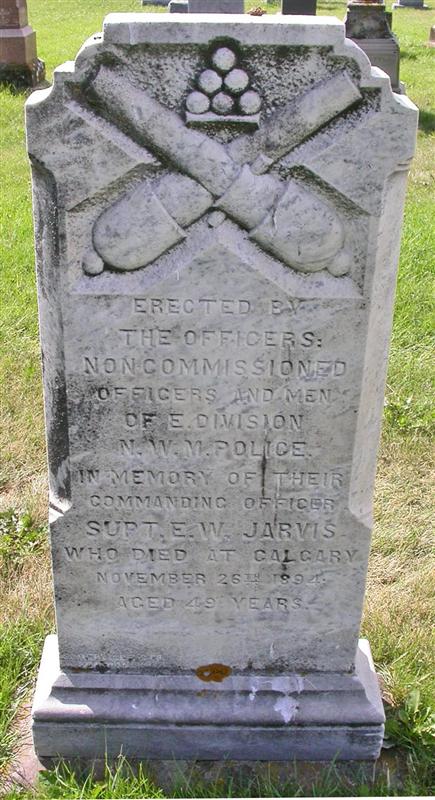

1868 dated photo: Sitting: Bertha’s sister Margaret Pennefather Stukeley Gray (1845-1941), who married Artemus Lord and continued to live in Charlottetown. Behind her is another sister, Florence Hope Gibson Gray (1848-1923) who married Henry Skeffington Poole and moved to Stellarton, Nova Scotia with him, and later in retirement to Guildford, England. The man is their cousin Edward Worrell Jarvis (1846-1894), son of Edward James Jarvis and Elizabeth Gray. Jarvis went on to an extraordinary career as an engineer, railway designer, militia soldier, lumber executive and mounted policeman.

The Gray family was comfortable financially but not wealthy. Years later, she told her daughter Helen that as a young girl she envied Frederick Peters and his brothers at Sidmount House because each boy was treated to his favorite dessert on festive occasions, while she was never presented with a choice.

Bertha`s husband Frederick Peters with daughter Mary Helen Peters, their first child, born August 31, 1887 in Charlottetown. Family collection.

All seats of St. Paul`s Church in Charlottetown were filled on October 19, 1886 for the marriage of Bertha Gray and Fred Peters. The Examiner reported the union of “one of Charlottetown`s most popular and rising young barristers to one of Charlottetown`s finest daughters.“ Following the ceremony, the bride and groom left for a three-month honeymoon in England before settling in their Westwood home purchased from the Hon. Daniel Davies. In future years, Bertha`s fondness for England continued, as she took every opportunity to travel there for extended stays, particularly in London, in her mind the Centre of the Universe.

The last Gray sister to wed was Mary, who in June 1888 married Montreal lawyer William Abbott, son of future prime minister Sir John Joseph Caldwell Abbott. Actor Christopher Plummer is a grandson of William`s brother Arthur Abbott.

August 1887 saw the birth of Mary Helen Peters, first child of Fred and Bertha. She would always be known by her middle name Helen. The first son, Frederic Thornton Peters, born in 1889, gained the nickname “Fritz“ because of his great interest in toy soldiers and armies. John Francklyn “Jack“ Peters was born in October 1892, and then the fraternal twins Gerald Hamilton “Jelly“ Peters and Noel Quintan Peters were born on November 8, 1894 – exactly 48 years before the action in Algeria where their brother Fritz would earn the Victoria Cross. In 1899, after the family moved across the country to Oak Bay on Vancouver Island, another daughter, Violet Avis Peters, was born.

Children Helen, Gerald (holding cat) and Noel in Victoria, circa 1905

Fred Peters worked in a law partnership with his brother Arthur Peters and Ernest Ings. He gained a seat in the provincial legislature in 1890, and within a year became leader of the Liberal Party, and then premier and attorney-general. Despite political success, the family was experiencing financial woes, as the Cunard inheritance received by Fred’s mother Mary Cunard had run its course. Fred desperately wanted to improve his finances, as he and Bertha expected to continue to live to a style to which they had become accustomed.

Son Frederic Thornton Peters, known to family and friends as Fritz, in 1901 in Bedford, England.

Bertha came to her marriage with high expectations, and was not pleased to hear of money problems. Her demands that the children be educated at private schools in England were likely a factor in her husband abruptly resigning as premier in mid-term in October 1897 so as to earn higher income in far-off Victoria, B.C.

In raising the children, Bertha was the strict parent, emphasizing discipline and the importance of living up to the traditions of the family and the British Empire, while Fred was an affectionate, sentimental father who read stories to his children and tucked them into bed at night. She saw no need to treat her children equally, choosing Gerald as her favourite and Noel, who had a moderate mental disability, as her least favourite.

Early in the First World War she decided to travel to England on her own to be close to her sons in military overseas service, particularly Gerald, who was her best friend and soulmate as well as favoured son. By the time she arrived in July 1915, Private Jack Peters had died four months earlier in the Second Battle of Ypres, but was listed as missing and believed to be a prisoner of war. In late May 1916, while staying at a rented cottage near Dover where she hosted Lieut. Gerald Peters on his leaves, word came from Germany via the Red Cross that Jack was definitely not a P.O.W., so was assumed to have died in action 13 months earlier. Just a couple of weeks later she learned that Gerald was missing following a June 3, 1916 counterattack at Mount Sorrel, also in the Ypres Salient. Four weeks later his death was confirmed.

Lieutenant Gerald Hamilton Peters, spring 1916

Engulfed by despair over Gerald’s death, Bertha went to stay at her sister Florence Poole’s home in Guildford before returning to Canada. As was common at the time, Florence indulged in spiritualism as a means to contact dead loved ones in the afterlife. Bertha began participating in séances as a way to contact Gerald, which infuriated her son Fritz who saw her spiritualism and excessive grieving over Gerald as signs of weakness at a time when maximum strength was needed to defeat the enemy.

Returning to British Columbia in November 1916, Bertha couldn’t bear to return to the family home in Prince Rupert because it was full of memories of Gerald and Jack, so instead went to live with her daughter Hel en Dewdney’s family in the mining town of New Denver in the mountainous West Kootenay region of southeastern B.C., while husband Fred continued alone in the isolated port of Prince Rupert serving as city solicitor and city clerk. After Fred’s death in 1919, she lived permanently with the Dewdneys.

The last time she saw her Fritz was in July 1919 when he came back from England to organize his father’s funeral in Victoria, B.C. She and Helen had only indirect contact with Fritz until receiving a letter from him in March 1942.

As a widow in her fifties, Bertha tried to earn income by writing novels and short stories, but all were rejected by publishers. Using recipes and cooking skills from her P.E.I. heritage, Bertha often cooked for the Dewdney family, who generally enjoyed her meals but were on edge because, as a perfectionist, she would erupt in anger if something went wrong with the dinner.

Bertha, circa 1905

In a family of bridge aficionados, Bertha stood out as the best player, constantly striving to improve. She rated each community in the Kootenay region by the quality of their bridge players.

Bertha, circa 1910. Family collection.

Bertha was in good health until a fall down stairs in about 1935 left her a bedridden invalid. As the only child left in the house after her siblings left for marriage and university, Dee Dee became Bertha’s caregiver and audience for her stories and ideas about history and politics. Her chores included daily trips to the Nelson library to borrow or return books requested by her grandmother.

After Fritz’s death in an air crash on November 13, 1942, Bertha wrote a flurry of letters to England to find out more about the action in Algeria on November 8th for which Fritz would receive the Victoria Cross and U.S. Distinguished Service Cross. Separately, she asked Fritz’s friends to fill her in on Fritz’s life between the wars.

She was thrilled to hear from the British Admiralty office that Fritz would receive the Victoria Cross, but later was flabbergasted that the Americans went all out in honouring her with a full presentation ceremony for their DSC medal, while Britain just sent the VC medal to her in the mail.

Bertha after suffering a crippling fall down stairs at the Dewdney home in Nelson, B.C. in about 1935. Family collection.

Passing away July 30, 1946, Bertha was the last surviving daughter of Col. Gray. Harriet died in London in 1882, Florence in Guildford in 1923, and Mary in Montreal in 1936. Margaret, the only daughter to remain in P.E.I., was in excellent health until her death at age 96 in Charlottetown on December 31, 1941.

Inspired by her grandmother Bertha/Dally, Dee Dee became a professional librarian, and was an enthusiastic monarchist and anglophile. Travelling to England in 1953 for the coronation of Queen Elizabeth II, she often mentioned in letters home that she wished her grandmother was alive to share the experience.

Today, when people ask me why I buy so many books on England and the monarchy, I lay the blame on my great-grandmother Bertha/Dally!

Bertha left a wealth of family letters in family files through her lifetime, which were subsequently looked after by her daughter Helen Dewdney, Helen’s daughter Dee Dee McBride, and now me. In addition, in June 2020 I came in contact via Facebook with a lady in Alberta who had lived in the former Dewdney/McBride home in Nelson, B.C. in the 1980s, who discovered about a dozen additional letters in floorboards when they were renovating the house. I greatly appreciated receiving the letters, which add substantially to our understanding of Bertha’s situation in the very stressful months of late 1916. Most of them were sent to her from her sister Florence Poole in England, and include discussion of spiritualism, mediums and seances, which children Helen and Fritz disapproved of her practising as a means to contact son Gerald in the afterlife.

envelope of 1916 letter sent by Florence Poole to sister Bertha Peters, part of the stash of correspondence discovered in the 1980s and received by me in 2020.

1911-1916 envelopes and front pages of letters to Bertha Gray Peters. Discovered in 1980s and forwarded to her great-grandson in 2020.

Sources:

The family history writings of Florence Gray Poole and Helen Peters Dewdney, and letters received by Bertha Gray Peters, in the Peters Family Papers; various newspaper accounts; One Woman’s Charlottetown: Diaries of Margaret Gray Lord 1863, 1876, 1890; census, vital statistics and ship records; and the author’s recollection of family discussions.

deluxe cover of souvenir Mountaineer

deluxe cover of souvenir Mountaineer inside cover

inside cover opposite page of inside cover

opposite page of inside cover 1

1 2

2 3

3 4

4 5

5 6

6 7

7 8

8 9

9

16

16 17

17

27

27

38

38

64

64

98

98 99

99

back cover

back cover